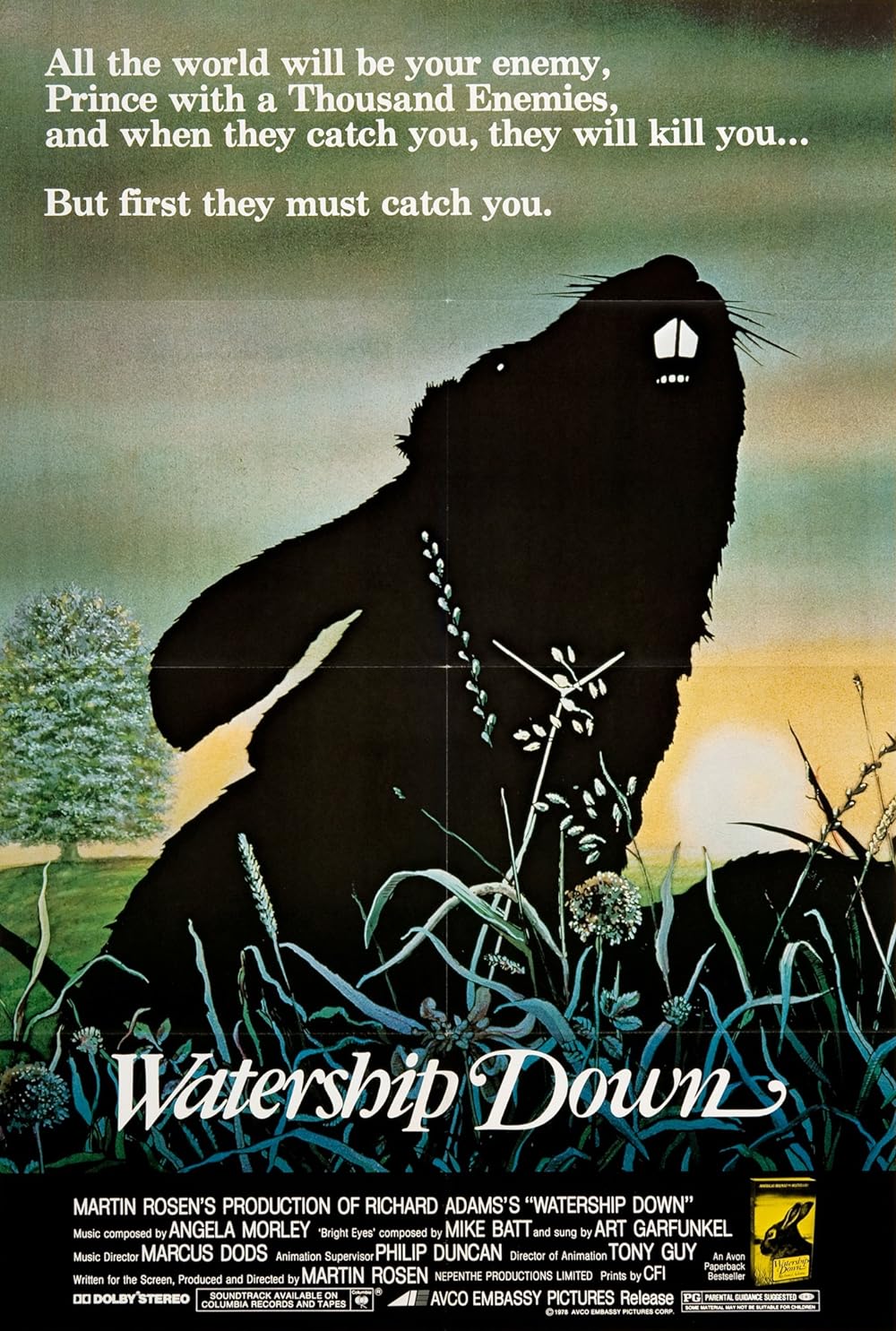

Starring: John Hurt and a smaller role from Zero Mostel

Grade: B-

Above all else, Watership Down succeeds in creating cool character names for every single animal in the movie. What’s more inventive than names like Hyzenthlay and Blackavar? Nothing that’s what!

Summary

Within Lapine mythology (a mythology created by the rabbit characters in Watership Down), the god Frith created the world and the stars. Along with this, he created animals and birds. At first, they were all made the same. Among the animals was El-Ahrairah, the prince of rabbits. He was friends with all of the animals, and they all ate grass together. After some time, the rabbits started multiplying everywhere and eating everything as they went. This bothered the other animals, prompting Frith to give El-Ahrairah an ultimatum. If he can’t control his people, Frith will find ways to control them instead. El-Ahrairah refused to listen and boasted how his people were the strongest in the world. This pissed off Frith, so he gave a present to every animal and bird, making each one different from the rest. All of a sudden, there were foxes, dogs, cats, hawks, weasels and others, and they were given the desire to hunt rabbits from Frith. A lot of El-Ahrairah’s fellow rabbits were slaughtered as a result, and he started seeing visions of the “Black Rabbit of Death”. He hid headfirst in a hole, with his legs and bottom sticking out. Seeing this, Frith acts like he doesn’t know it’s El-Ahrairah and asks if he’s seen him because he has a gift for him, though El-Ahrairah replies “No”. He tries to offer the present, but the rabbit refuses to get out of the hole on the account of the other animals pursuing him. He says if he wants to bless him, Frith will have to bless his bottom. Frith obliges. He gives him a white tail and lengthens and strengthens his back legs to make him one of the fastest animals on the planet. Frith makes it clear that all the world will be El-Ahrairah’s and his people’s enemy.

If they catch you, they will kill you…

…but first, they must catch you.

As long as rabbits stay cunning, they listen, they run, and continue to be full of tricks, they will never be destroyed.

In the present day, rabbit Hazel (Hurt) exits a bush and tells his younger brother Fiver (Richard Briers) the coast is clear, though Fiver is anxious because he’s feeling uneasiness in the air. Regardless, Hazel enlists Fiver in helping him find some food. However, when Fiver does find the specific plant that they were looking for, two other rabbits in their collective burrow claim it on the grounds of the rules they have set in place. Annoyed, Hazel and Fiver carry on. Hazel finds some food, but Fiver wanders nearby. He sees a big wooden sign and a cigarette on the ground. This is when he realizes that his anxious feelings are more of apocalyptic one’s. Though Hazel sees the field ahead of them for what it is, a sun hovering over some trees, Fiver gets visions of the field covered in blood. As he talks about the danger being all around them, Fiver insists that the entire warren needs to leave the area to escape the incoming danger upon them. Hazel isn’t entirely convinced, but he takes him to go see the Chief Rabbit (Ralph Richardson). On the way there, Fiver can’t help but alert the rest of the burrow about this unknown danger and how they need to get out of there, so now everyone is interested and following them. Hazel and Fiver wait outside of the Chief’s tree to ask Owsla police force member Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox) if they can see him. Around the corner, Captain Holly (John Bennett) sees the two and tells Bigwig to send them away. However, Hazel is able to convince Bigwig because he’s never asked to see the Chief before. Once he gets permission, Bigwig lets them both into the hole in which the Chief lies. All of the other rabbits that Fiver alerted wait outside of the hole and try to listen in. Fiver explains the situation to the Chief, but with little to go off of other than “Something bad is going to happen” and “We need to leave now”, Chief is not particularly convinced since it’s May and its mating season. Hazel tries to argue that Fiver has had these feelings before, and he’s always been right. Though the Chief considers taking it under consideration, Fiver freaks out and leaves because he knows this will be too late, with Hazel following him.

As soon as they leave, Chief gives Bigwig a bunch of shit for letting these two “lunatics” inside.

That night, Blackberry (Simon Cadell) and a group of others approach Hazel and Fiver because they heard they were leaving the warren from Dandelion (Richard O’Callaghan). They all want to come with. Together, the group begins their trek. To the side, we can see Fiver’s visions of danger were true. Though none of the rabbits can read, the nearby sign says, “This ideally situated estate comprising six acres of excellent building land is to be developed with high class modern residences…”.

The group are spotted by the Owsla police force, so they try and go faster, only to run into Bigwig. Thankfully, he’s off-duty and he’s decided to leave the Owsla. Its clear Fiver’s rants have gotten to him. Out of nowhere, Captain Holly jumps in and tries to put them under arrest for spreading dissension and inciting to mutiny. Hazel threatens to kill him, so Holly bites him in the neck. This forces Bigwig to jump in and attack Holly. Seeing he’s outnumbered, Holly leaves to get the rest of the Owsla. Knowing there’s nothing left for them here, Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig, and the rest of the crew head out. Sometime later, Bigwig tells Hazel privately they should camp out for the time being because the others need to rest. Hazel declines, saying they need to get past the woods to be clear of the Owsla. Then, they can rest. None of them have been through a forest before, and they are all freaked out by the other predatory creatures watching over them. Even so, they get through it and travel through the night. Eventually, they reach a crossroads at a lake. Fiver insists they have to cross it, but he’s too tired to swim, as is Pipkin. As he talks about the goal being a “high, lonely place with dry soil where they can see and hear all around and where men hardly ever come”, Bigwig alerts everyone of a loose dog in the woods. They need to act now. He tells the rabbits who can swim to do so. The others will have to figure it out. Hazel refuses this because it should be a team effort. Blackberry finds a lone plank of wood, and they notice it can float on the water. So, they quickly place Fiver and Pipkin on the plank, and Bigwig and another push it with their noses while they swim across. All of the other rabbits swim by themselves, and they all manage to make it across safely. The dog is whistled back to its owner right when it gets near the water.

As they leave, Hazel compliments Blackberry on the idea, and Blackberry tells him they should remember it in case they have to do it again.

They continue to travel. At one point, they cross a street and find roadkill. Bigwig explains it’s the doing of a car, but they aren’t a worry to them because they don’t pay attention to animals like them. He demonstrates by standing on one side of a lane with a car driving right past him, though another car almost hits him going the opposite way. Later, they see a scented field that will cover their sight and sound long enough for them to rest for a bit. They camp out and nap in the middle of the day. Violet wakes up and goes to check out a flower outside of the field. Fiver wakes up and notices her but is stunned to see a hawk fly and snatch her away in an instant. The other rabbits wake up, and Fiver relays the sad news. Hazel decides they need to keep moving, so they go. Sometime later, Bigwig again tells Hazel they need to rest everyone, so Hazel suggests a nearby cemetery. Bigwig thinks it’s a “man place”, but Hazel insists there are no men there anymore. They all sleep inside the groundskeeper’s building but are waken up in the middle of the night by rats and an owl threatening them and causing a disturbance. After this, they deal with the rain and unrest from the rabbits begin. Some even consider going back to the warren. As Hazel promises them that they’ll reach their unknown destination soon enough and Bigwig reminds them all how they can’t go back because they’ll probably be killed for the attack on Holly, Fiver interrupts to say they need to reach the hills. He then adds that “those that go back will not…not safe”. The other rabbits still seem to get in Hazel’s face and accuse him of not knowing where they’re going, so Bigwig steps in and backs him up.

Everyone is interrupted by Cowslip (Denholm Elliott), a rabbit belonging to the warren near the field they’re on. Cowslip is oddly friendly and talks about how they have plenty of empty burrows for them to hang out in for a while if they need it. Bigwig gets defensive, but Cowslip offers his help and goes back inside. The rabbits are unsure what to do because of the suspiciousness of Cowslip, and Hazel wonders aloud what Cowslip may have to gain from offering such help. With the rain continuing and despite their suspicions, Bigwig leads them inside Cowslip’s warren. Upon getting inside, Cowslip invites them to eat some of the fresh carrots he has laid out because they come in daily from a man on the outside, though he dodges the question of where the other rabbits of his warren are when Hazel asks. Cowslip leaves them alone as they eat, and other rabbits from the warren listen in on Hazel and company talk aloud about the eeriness of this whole situation, with Fiver getting feelings of being deceived. Eventually, Cowslip interrupts again to ask the group to join the other members from his warren on some storytelling session. Hazel tells Dandelion to tell a story about El-Ahrairah, but Cowslip puts this down as something they don’t really give a shit about, passing it off as “charming” and nothing more. Instead, Cowslip starts quoting poetry, and it’s finally enough for Fiver to leave the burrow entirely. Hazel tries to stop him, but Fiver is fixated on reaching the hills. When Hazel mentions he’ll die travelling alone, Fiver responds by saying Hazel and everyone else are closer to death than he is. Bigwig comes out and calls Fiver selfish and goes back to ruin everyone else’s opinion of him out of principle. Suddenly, they hear a squeal. Hazel and Fiver go over to find that Bigwig has been caught in a trap and is being choked to death.

Hazel sends Fiver into the warren to get the others for help. Their group of rabbits come, but Cowslip and his rabbits refused. He even told Fiver to stop talking about it. The rabbits see the wire that’s choking Bigwig is on a peg, so Fiver is able to chew it enough for it to break in half. This frees Bigwig, but he passes out and is seemingly dead. Infuriated, the other rabbits consider war on Cowslip and his warren for refusing to help and how they can just take their burrow from them, but Fiver says it’s a deathtrap. Just then, Bigwig awakens, and everyone calms down. They ask Fiver what’s next, and he points out the massive hill in the distance, what we know as Watership Down. Though it’s a long way, it could be everything they could ever want. United, the goal is to make it to these lonely hills. It seems simple enough. Unfortunately, even when they do get there, the rabbits soon realize that this isn’t the final phase of their mission, as some much-needed evolutionary elements are still needed to complete their new warren. With a new goal in mind, the risk of death is waiting for them at every possible angle and puts them in more danger than they have ever faced before.

My Thoughts:

In a world of sugarcoated Disney features that focus on overt sentimentalism, fun action without getting too violent, over-the-top characters, and nothing more than implications regarding the discussions of serious topics, Watership Down engages with the same demographic but instead goes deep in the direction Disney never dared to go because of their fear of losing its label of dedication to family-friendly content. While still making an animated adventure that is both heart-pumping and graphic, this British drama helmed by Martin Rosen dares in its maturity, its realism, and its rare and undaunting look behind the curtain of the wildlife around us, showcasing the vicious everyday happenings of nature not seen in animated features before or since.

Nature can be brutal. In live-action films, we know this. There are countless movies where man is faced with danger because of the threat of outside elements and wild animals on the hunt. There’s one released virtually every year. It’s that prevalent. You could make a list right now of this subgenre of movies, and it would probably be the size of a nice chapter book. On the flip side, how many animated films talk about the haunting reality of how animals actually act in the wild? Could you even make a list? Everyone knows how popular cartoon animal-themed movies are. We love watching their wild adventures, and the more anthropomorphized they are, the more outrageous and funnier the story turns out to be. It’s even amusing to see them wearing human clothes and doing normal things because it’s so out of the ordinary. However, there are so many animated tales that do this now, it’s almost expected. With Watership Down, we go back to the basics and it’s somehow a breath of fresh air. Though a product of the time and not as inventive as a Disney movie, the watercolor landscapes give off the feeling of nature at its most authentic. The burrows dug, the forests and lakes travelled through, and the fields in which the rabbits lie are lifelike, and they aid us in understanding the difficulties of the trek our furry friends face. The hill of Watership Down itself is blissful in its presentation, despite its reality being that of a giant hill. Even so, the viewer feels at ease when they see it just as the characters do because of how well-done the buildup is in this smaller-budgeted, “regular” movie, when in comparison to its counterparts. This is an indicator of great direction through and through. CGI and computer-animation can do some truly amazing things on film, but there’s something nostalgic and downright beautiful about a movie like Watership Down and how it stresses the importance of the characters’ rather simple destination of something we would take for granted as humans.

During this runtime, we see the beauty and the horrors of nature and life in general through the perspective of rabbits, and director Martin Rosen handles the material given to him from Richard Adams’s book with care, love, and respect.

When speaking of the animated tales of its peers, Watership Down struggles with one crucial thing. The characters are drawn with no imagination. It’s realism approach to the character designs are admirable and it makes sense because if you went too far in the opposite end, it would distract from the maturity of the story. However, it was a tad too bland. With the exception of Fiver, it’s very difficult to tell any of the main characters apart. You can kind of decipher through the voice acting, but it’s a real struggle. It gets even harder when they have a few minor characters talk in the midst of a discussion because you have no idea who said what unless you were watching intently. The Hitler-like General Woundwort’s design was as striking as a villain should be. Through a harrowing vocal performance from Harry Andrews and a darkly memorable look to accompany it, Woundwort terrifies when he’s onscreen and exudes the power he is said to have merely by his presence. As soon as the character is introduced, the audience knows exactly the threat he poses to the main characters. It’s a picture-perfect presentation as far as antagonists go, but how come it takes half of the movie to tell the difference between Hazel, Blackberry, and Dandelion? Why do such an excellent job with the secondary characters but draw the main characters and good guys in the most plain way possible? You don’t have to give them big eyes or a t-shirt or something. All you need to do is just draw them a little bit different, so kids and even adults alike can easily spot who someone like Hazel is and we can tell right away who’s been shot in the heat of the moment. Whether it be a birth mark or someone having ears that are lower than everyone else’s, something needed to be done for the viewer to easily decipher who is speaking. This way we can have a personal connection with each character. The design doesn’t have to be as crazy as Woundwort, as he stood out more because the simple looks of everyone else, but there just needed to be something different with Hazel and the members of his warren for the sake of the viewing experience. Thankfully, Bigwig at least had hair, but everyone else gets lost in the shuffle.

Again, the designs of the characters are very realistic but almost unimaginative to a fault. Plus, everyone looks mad because their eyebrows are pointed down. Seriously, watch the movie and you’ll notice how all the main characters are designed to look absolutely miserable with the exception of Fiver, who looks scared all the time.

The droopy-eyed Cowslip was intriguing because of his design as well, though from a story perspective it seemed like he had a lot more to offer. His warren was as eerie as the others said it was, and he was way too calm considering the anxiousness of all the other rabbits in this movie. You’d think he was ready to trap the group and eat them cannibal-style with how off everything feels in the moment. Though it doesn’t turn out to be that bad, it’s still a dreadful outcome, as Cowslip’s group is completely okay with being picked off by the man who lives above them because he houses and feeds them every day before it’s time. It’s strange how at peace they are, but it explains Cowslip’s nihilist-like response when the others try to bring up El-Ahrairah. He has his food every day and a quiet home, so he’s at ease with how things are, despite knowing death can come at any time. His goal, which isn’t explained in the movie nearly as well as it is in the novel, is bringing in others to be slaughtered to give himself and his cohorts another day to live, which is why they have so much room in their burrows despite being nice rabbits on the surface. It’s a real prick move, but this was yet another interesting development that I just couldn’t help but think there should have been more time given to explore further. If anything, a potential pre-battle before the big one with the Efrafans felt necessary. Unfortunately, Rosen is at the mercy of how the novel went, so I get it.

Despite the viewer potentially being lost with which character is which, another major positive is the emotional connection we have with the Hazel and his group of rabbits. As a collective, you understand their plight. Death is at every corner. Such is the life of a rabbit. It makes sense why they believe in their Lapine mythology. Though some of the names used are outrageous and hard to understand, these animals re-telling these stories for generations to explain why they are disadvantaged creatures who are prey to so many animals makes a lot of sense. We can’t help but sympathize with these rabbits who now have to deal with the consequences of their ancestors for eternity, fighting to live and achieve the ultimate and almost unattainable goal of peace and tranquility when they are hunted and even oppressed like in the cases of the Efrafans. Everyone’s head is on a swivel, and we are drawn in emotionally to their goal because of how well handled the portrayal is of the genuine terrors they face within nature because of everyday things like dogs, cats, farmers, and even fellow rabbits. They have to trek in secret and when we see the violence they face from their world in the search of freedom, it feels somewhat inspired from what we’ve read about the Underground Railroad, or even a World War II movie with the way the story carries itself. Think about when Woundwort talks to Bigwig when he becomes an officer, and he tells Bigwig he can have the choice of any doe he wants because of his untouchable status much like the appalling behavior of slave traders doing whatever they wanted to the people they owned back in the day. Tell me right now it doesn’t feel like Hazel and the other rabbit trying to break Clover and her group out in time before the farm is alerted to their presence doesn’t feel like they are trying to escape a concentration camp in a high-octane war drama with a depressing ending?

You may not want to admit it, but the parallels are evident. The Efrafans were 100% Nazi-influenced, and you cannot tell me any different. Campion was a high-ranking SS officer without a doubt.

Religion is a major element of Watership Down, which I found very interesting. Hope should be gone in these rabbits because of how low on the totem pole they are positioned, but they still have an internalized will to keep going. Of course, this can be attributed to Frith, who is essentially God. This was yet another refreshing and intriguing layer included to expand the mythology of these rabbit characters and to explain what drives them to live life in the manner they decide to. When Holly talks about how he only escaped the Efrafans because “Lord Fritz sent one of his great messengers”, the flashback shows us the divine intervention of a train passing through during the chase that killed the rabbits following him. It’s the equivalent of someone in real life saying after a near-death experience that “An angel was watching over me”. When Bigwig is believed to be dead after being choked by a snare, Hazel immediately says in prayer, “My heart has joined a thousand, for my friend stopped running today”, and it’s powerful, despite the meaning not being very clear. The fact that this is the first thing he decides to do shows us how important their beliefs are. When Hazel instills confidence in his fellow rabbits and attempts his last-ditch effort to stop Woundwort with his “Loose dog” plan, we listen in on our hero’s private thoughts as he runs against time. Hazel is very aware he may die, but if things have to happen, he just asks for his life to be taken in return to save his fellow rabbits. Not only does it endear us to our hero who’s coming face to face with death in the upcoming minutes and knows it, but it presents their unofficial religious beliefs in a very heartfelt, non-preachy way that everyone can learn to respect. By the end, Hazel almost turns into a Christ-like figure because of his selflessness and earnestness as a protector of his kind willing to do whatever he needed to make sure his people lived. Though a teary-eyed response from kids is possible, it’s quite the beauty of an ending when looking at the production as a whole. Things went exactly as they needed to when taking every detail of the story into account and realizing how this was all rooted back to religion in a roundabout way.

With that being said, Hazel interacting with Fiver and Bigwig one more time would have made been nice, especially because of how massive of a help Bigwig was. Him going undercover with Efrafans was the ballsiest move there was and the most pivotal decision of the entire story. He’s just as important as Hazel was to this warren and earned the same spotlight as him in the closing moments. Why it was all about Hazel when this was a clear ensemble story of teamwork at its finest, along with a certain focus on great leadership, didn’t make any sense. Along with this, there are some other problems. Besides the grim realities of rabbit life being portrayed well, the fact that the second half of this movie can arguably be boiled down to the male rabbits facing life or death for pussy is a bit of a drag, though it’s funny that they completely drop the idea of saving Clover after that idea fails, and they just go and look for some other females to chase after. With that being said, if a younger audience is watching it, girls are not going to like this movie nearly as much as young boys well, but this is more because of the fighting. In their defense though, this is all a realistic presentation of the life of a rabbit. The idea of seeing the Black Rabbit and how it means death like when humans see the Grim Reaper was a nice touch, but the sequence where Fiver follows the Black Rabbit to find the wounded Hazel was poorly done. At one point, they do the same exact art sequence almost frame by frame as the sad music plays, and it takes the emotion out of the moment completely. Honestly, there’s a lot of redundant aspects of the movie as a whole. If you’re not in the mood, you may not be nearly as invested in the scariness of real nature because it could feel a bit repetitive until the injured Holly shows up to warn them about the Efrafans. I don’t share this sentiment, but I could see this being a criticism depending on the age or attention span of the person who watches it. Also, did Hazel really think coming to a ceasefire with Woundwort was a real possibility? What a waste of time that was.

Kehaar is the only goofy, Disney-like character in the movie, and he stands out MAJORLY because of it, but this is a good thing. Zero Mostel is hilarious in the role. He sounds as if he struggles to get out every word in his thick accent, and he garners a laugh almost every time he spits out a jagged statement while randomly screeching or eating a nearby fly or insect. If he doesn’t win you over with his first words of “PISS OFF!”, he’ll do it eventually when the war commences in the heart-pumping escape sequence. He’s pivotal to the entertainment value of the production, and it’s guaranteed that he’ll leave you wanting more of him.

There is no doubt that Watership Down is a more mature animated movie akin to something like Animal Farm, but it’s nothing a kid can’t handle. If anything, it can open their eyes to what animation can actually be, a serious art form that should not be pigeonholed with the label of “low-brow children’s entertainment”. Admittedly, Watership Down is a violent adventure with a somber tone and a reality check of death or injury at every turn (RIP Violet), but this is why the movie stands apart. It thrives because of its courage to be grounded in realism and risks it all in doing so. At the same time, it brings Richard Adams’s imaginative and thrilling story to life while bravely exploring more adult topics like survival, life-threatening moments, religion, and the afterlife. Not every kid will be along for the ride because they’re too accustomed to the snappy, eye-popping, colorful fluff most studios produce in the animation department. However, an age group willing to sit down and listen can really appreciate the story being told before them. By the time the showdown commences between Bigwig and the evil General Woundwort, and it’s intercut with the dog chasing the rabbits back to the warren, the pure adrenaline stemming from it is organic as they come. It may not be better than the other classic animated productions of its time, but Watership Down is an under-the-radar gem with a lot of value because of its distinct style and unique narrative.

+ There are no comments

Add yours