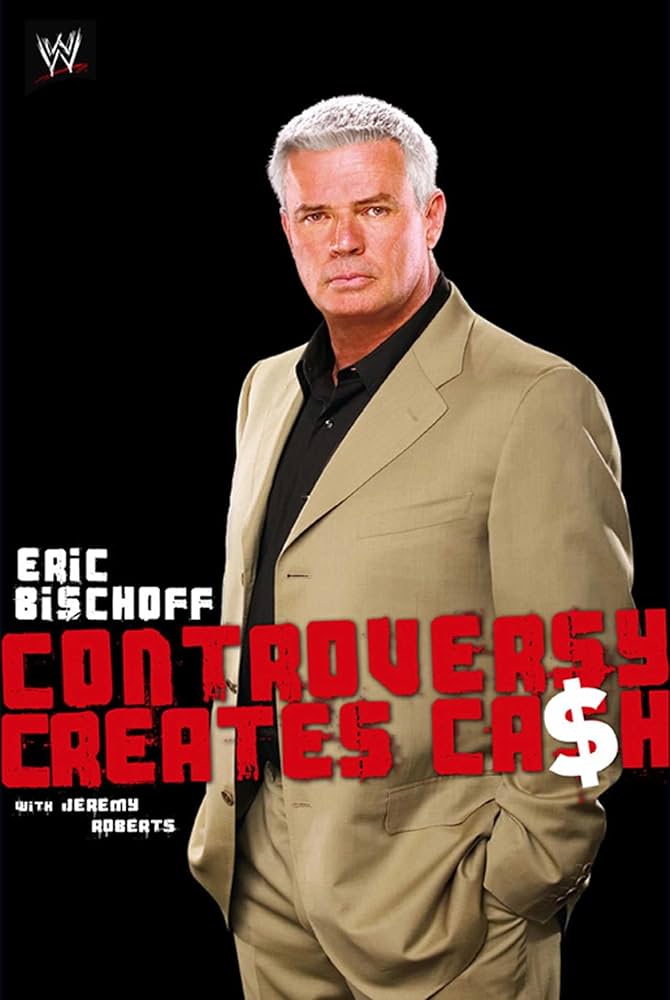

Written by Eric Bischoff with Jeremy Roberts

Grade: A+

“Managing success is sometimes much more difficult than creating it in the first place”.

Man, what an understatement.

Summary

The “Dedication” portion opens the book. This is where Eric Bischoff talks about how he never wanted to write a book about his life in wrestling because he felt as if his story wasn’t that interesting. After some time had passed and he started to see the evolution of sports entertainment however, he began to appreciate what he did because of how pivotal it was to changing the industry. With this, he dedicates the book to his co-writer Jeremy Roberts, as Roberts spent countless hours with Bischoff helping him remember, organize, and structure his story to create Controversy Creates Cash. Along with Roberts, he dedicates the book to his wife Loree and his mother. The latter beat cancer and he just got the news that it came back.

In the Prologue (“Give Me a Big Hug”), we set the scene for Eric Bischoff’s debut on WWE television. It’s July 15, 2002, in East Rutherford, New Jersey, and Bischoff is in the back of a stretch limousine in the parking lot of Continental Airlines Area. It’s big night because he’s debuting on the company he almost put out of business and is working for the man he went head-to-head with previously in Vince McMahon. McMahon enters the limo. After asking Bischoff if he’s nervous and Bischoff says he isn’t and rather excited, they go over the plan on how they are going to debut his character on television that night. Keep in mind that this is only the second time in his life that he’s met McMahon in person. The first was more than a decade before when McMahon greeted him after a job interview for the former WWF in Stamford. Bischoff didn’t get the job, but he admits he didn’t deserve it. Had he did get the job, wrestling would be a lot different than what it is today. Even so, McMahon details the plan of what’s to commence. When he announces the new general manager of WWE’s flagship show Monday Night Raw and Bischoff’s music plays, he wants Bischoff to come out, acknowledge the crowd, shake his hand, and give him a big bear hug. Once McMahon exits the car, Bischoff reminds the reader that there was an announcement that Raw will be getting a new general manager, “one guaranteed to shake things up”. He notes how much of an understatement this is, and wrestling fans will see it the same way. Next, Bischoff talks about Raw and how a lot of major components of the show are elements stolen from Bischoff’s prime time show Monday Night Nitro when he was running WCW for the TNT network. Things such as the two-hour live format, its backstage interview segments, and reality-based storylines all originated on WCW programming. When Bischoff had the reigns of the WWE’s rival, they kicked WWE’s ass for three years. The media called it the “Monday Night Wars”, but Bischoff refers to it as more of a rout since Nitro beat Raw in the ratings “eighty-something” weeks in a row.

He acts like he doesn’t know the exact number, but he has a podcast today called 83 Weeks with Eric Bischoff, so don’t let him fool you.

Anyway, he says the real battle began when McMahon caught on to what they were doing over in WCW and evolved his own show. However, Bischoff explains the less talked about facts concerning the ACTUAL battle he faced. Of course, this was between WCW and the “corporate suits who took over Turner Broadcasting with the merger of Time Warner and then AOL”. It was a fight “I was never capable of winning, though, being stubborn by nature, I didn’t realize it until it was nearly over”, according to Bischoff. At this point, Stephanie McMahon pops her head into the limo to ask if Bischoff is nervous, but he reiterates his excitement. He’s about to walk into an arena filled with people who hate him, but more accurately his character. Bischoff goes on about how it’s hard for people to make a distinction between the two or how people think they know who he is based off what they read on the Internet or on dirt sheets, the newsletters that cover the wrestling business for fans. There are also wrestling fan sites that don’t have a foot in the business and create their own stories for reactions, resulting in a lot of misinformation being floated around. Part of this was why he decided to write Controversy Creates Cash. He admits he doesn’t like most wrestling books because “most are bitter, self-serving revisionist history at best and monuments to bullshit at their worst”. Additionally, a lot of the guys that write them want the last word or bring up old battles that everyone but them has forgotten. He calls them all whiners and insists that’s not him regardless of his bumps in the road. No matter what, he still loves what he was able to accomplish in pro wrestling. He started out as a salesman and became an on-air talent (“by necessity rather than ability”). Then, he somehow managed to become chosen to head the second largest wrestling promotion in the country. At that point, they were a distant second to McMahon’s WWF at the time and were bleeding money every year. Behind Bischoff, they became number one. WCW was a company generating $10 million in losses on $24 million worth of revenue, but Bischoff was able to make the company $350 million in sales and getting $40 million in profit. After all this, then things fell apart.

Following this wild series of events, he’s right back to where he started as an on-air talent, though it’s with a guy he was at war with. Despite this, they still became friends.

Stephanie McMahon takes Bischoff out of the car because he’s about to be on, and they walk through the backstage area. Some of the wrestlers who see him are in shock. Before he goes out, the two-page script he was given to memorize bounces in his head. Before this, he always improvised, but the WWE is different.

Next, Bischoff goes on an aside about how wrestling began in the United States as a sideshow carnival attraction that grew on showmanship, unique characters, and illusion. Part of that remains today. Now, “no other form of entertainment, quite frankly, combines the different revenue streams and opportunities that WCW had, or that WWE has now”. The idea behind this book is to give some insight into this aspect of the business, as what happened in WCW was just as much about business as it was wrestling. Wrestling fans point fingers at the guaranteed contracts for wrestlers or Hulk Hogan having creative control over his matches and overpaying some wrestlers as being among the reasons that put WCW in a place that was hard to get out of financially. It’s true, though this wasn’t the reason WCW failed. Bischoff even argues that the talent budget could have been half of what it was, but it made no difference. Everything came crashing down from the inside when Time Warner bought Turner. Turner’s merger with Time Warner, and the subsequent merger with AOL was “the single largest disaster in modern business history”. WCW was just a casualty. He does admit his mistakes but he’s tired of hearing how he overpaid wrestlers and wanted to go Hollywood and such because this wasn’t the case. He’s confident in saying that if he wasn’t involved in the company, WCW still goes down as a casualty and it may have even happened faster. All of this is a cautionary tale about not only wrestling and entertainment but about what happens to creative enterprises and individuals when they “get caught in the maul of a modern conglomerate” and the Wall Street expectations that are commonplace today. Bischoff knows he’s not going to convince every reader that his book is the truth, and he might be remembering things subjectively, but all the stories previously written about WCW were from people who weren’t there.

Bischoff is introduced on Raw and embraces McMahon on stage. As it happens, he tells McMahon, “That rumbling beneath your feet is a whole lot of people turning over in their graves”.

Chapter One (“Throwing Rocks”) begins with Bischoff talking about being born on May 27th, 1955, in Detroit, Michigan, how he lived there until he was 12, and that he hated it. They lived in a lower-middle-income area, and it wasn’t great. His hardworking father Kenneth was born prematurely in 1930, and his spinal cord hadn’t developed properly, as there was a hole at the top of his spine and it filled with liquid when he got older, resulting in debilitating headaches. Still, he loved the outdoors and spent a lot of time hunting and fishing. Bischoff’s mother Carol was a housewife and took care of him, his younger brother Mark, and his sister Lori while his dad worked as a draftsman at American Standard. Around the age of 5 or 6, Bischoff’s father had brain surgery to try and relieve the pain. Though it got rid of the headaches, he had no use of his hands and limited use of his arms. He couldn’t even brush his teeth. He had to quit being a draftsman and became a purchasing agent, though he became bitter. Basically, it turned into Carol taking care of everyone in the house. There was also Agnes, who was Kenneth’s mother. She was rough and a big smoker. Anyway, Bischoff went to Dort Elementary School, which was the same one attended by Eminem years later. It was a tough school in a bad neighborhood, and he hated every subject except geography and history. During this timeframe, one game the kids would play was “army” because of shows like Combat! and 12 O’Clock High romanticizing World War II. The kids would choose the side of the Americans or the Germans and would throw literal rocks and clumps of dirt at each other. When he was 8, he discovered professional wrestling. Since his father had to work Saturday mornings, Carol would drive him to work, drop Agnes off at his aunt and uncle’s, and go grocery shopping. Eric would stay at home with Mark, they’d watch cartoons, eat ice cream, watch Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, and Big Time Wrestling on CKLW on Channel 9. There, he saw stars like The Sheik, Killer Kowalski, and Bobo Brazil.

Bischoff and Mark would wrestle and even script things out to practice them in slow motion. This was during the Territory Era of professional wrestling, where each territory had their own “world champion” but not everyone had cable, so they didn’t know about the other territories. Even though it was starting to be televised, wrestling was still close to its roots as a carnival sideshow. Kayfabe ruled the industry. For those that don’t know, kayfabe is the “private language used by those in the business”. He got his first job around 6-8 years old at a grocery store for an Italian couple picking up litter in the parking lot and around the store. When he was done, he could reach his hands into the cash register and was given all the coins he was able to grab in one try. He would later start sorting and stacking returned bottles and has been working ever since. Around fifth grade, he was in a fight every day and rarely won, as per usual living in Detroit. It only escalated when he got older, and a lot of kids would bring weapons like lead pipes and knives to school because of it. On his last day in Detroit, Bischoff brought seven dollars to school. Considering lunch only cost thirty-five cents at the time, you were essentially asking to be robbed. Knowing it was his last day and he’d be a target with the money, he made it known he had that much money on him. His last class of the day was shop class, and the teacher left early, prompting a kid to confront him. Waiting for this, Bischoff pulled a metal handle from one of the vises and nailed the kid in the head with it. The bell rang and it was time to go home right after, and he went out a legend. Bischoff and his family moved to Penn Hills, Pennsylvania the next day because his dad got a job opportunity in Pittsburgh. It was a major step up from where they were living in Detroit, with a finished basement and a lot of spacious area in the woods for activities. During this timeframe, Saturday morning wrestling was replaced with Saturday night wrestling, and Bischoff started to realize how there were different world champions in every part of the country.

In Pittsburgh, Bruno Sammartino was the champion. He was really popular in the area because of his workingman character, as it represented the blue-collar city. Sammartino was also local and lived near them. Though the kids would ride their bikes over to his place to catch a glimpse of Bruno, they never saw him. In school, Bischoff became a wrestler and started out in the 126-pound weight class in junior high, though he was average according to himself. At the same time, he continued to work and was hired by his neighbor Bob Racioppi to do odd jobs and light construction around his house. He developed a close bond with him because Bob could do things with him that Bischoff’s father wasn’t able to do anymore. He also introduced Bischoff to martial arts, which would later become a big part of his life. He followed this up with his first job at a roofing company when he was 14. As his work ethic and confidence began to build, his father got a new job in Minneapolis. He didn’t want to leave since he established so much in Pennsylvania, but the family moved in 1970 when Bischoff was in tenth grade. The person who sold them their home in Minneapolis had a son on the wrestling team and he was able to help Bischoff get used to his new team and such. In a random anecdote, Bischoff talks about how he was never into drugs, though he was tempted to try speed once. A popular girl in school experimented with Black Beauties and she could hardly stand still in the morning. Later on that day, blood was coming out of her mouth because she was so messed up, she chewed the inside of her mouth bloody. That was enough for him to pass on the idea, as it would for most of us. He did try weed but found the whole experience a waste of time. One thing he did have a passion for was motorcycles. He had a minibike when he was 10 and graduated to motorcycles at 16. The craziest thing he’s ever done was try to jump his Kawasaki motorcycle. On his 4th or 5th attempt, he crashed midair into the side of a garage next to his friend’s house and messed up the bike. He still loves his motorcycles, but that was the last time he tried to jump one.

Eventually, his foray into the wrestling business began, but it started out in a way you wouldn’t expect. Wrestling legend and Minneapolis star Verne Gagne was a former marine and amateur college wrestler and started wrestling professionally in 1948. He founded the famous AWA in 1960. Within a few years, it became one of the country’s strongest promotions, promoting shows in the Midwest, Las Vegas, San Francisco and a few other smaller cities and towns. Its main program was AWA All-Star Wrestling and starred the likes of Verne, his son Greg, Nick Bockwinkel, Chief Wahoo McDaniel, Larry “the Axe” Hennig, Baron Von Raschke, Ray “The Crippler” Stevens, and others. Over the course of his high school wrestling career, Bischoff actually met Verne Gagne once or twice. He lived three miles down from where Bischoff lived. In his senior year, Bischoff’s AAU freestyle wrestling team was selected to compete against a team from Sweden that was touring the country. Since they needed to sell tickets to get the word out but had no money to advertise it, Bischoff called the AWA offices to maybe convince them to promote it. He managed to get in contact with Wally Karbo, gave him the basic details and offered to do an interview to let people know about their event to sell tickets, and Karbo agreed with no resistance. On a Saturday morning, Bischoff and his friends drove over to the Channel 11 building where the tapings were held, saw some of the roster members, and were sat in the studio. Not long after, Bischoff was brought onscreen for an interview with Wally Karbo and Marty O’Neill. This was his first appearance on television. Bischoff would continue working odd jobs in the meantime like running a Bobcat bulldozer, driving a dump truck, flipping pancakes, and working in an animal hospital. He was trying to collect money at all costs and was never interested in school. In the spring of 1973, Bischoff blew out his knee in a wrestling match in his senior year against some farm boy named Joe Boyer. He never had surgery on it and has reinjured it “probably two or three dozen times” since. Bischoff did wrestle later that summer, but his knee bothered him too much for him to work out regularly, ending his amateur wrestling career.

Though he never thought about college, he saw all his friends wanting to go, so he applied to St. Cloud State in St. Cloud because one of his best friends was going there. To his own amazement, they accepted him and he dormed with his friend. Bischoff didn’t take it too seriously though. All he did was party and work for a freight company unloading freight cars full of lumber. He had to drop out after his freshman year because he couldn’t afford it. Next, he transferred to the University of Minnesota so he could live at home and regroup his finances. Because of his experience in working for a landscape construction company, he ended up as a foreman during the summer before he went to college and got pretty good at building retaining walls and overseeing some of the larger commercial projects he was assigned to. By the time he was a sophomore in college, he started his own landscaping firm. He went into a partnership with a friend, and the two ended making the company one of the larger commercial landscaping firms in the area by 1975 or 1976. After getting a contract with the city of St. Paul that put them over the hump, they were soon getting an excess of a million dollars a year in sales. At this point, college was getting in the way, and Bischoff admits he was making more money than three of his professors combined. So, he dropped out and bought his first house at the age of 21, a block off the beach near Lake Minnetonka. He also bought a new car, but the business started to grow too much, and he stopped enjoying it. Soon, he wasn’t getting along with his partner either, so he sold his half of the company and took a break to find his new passion in martial arts. He started taking classes in taekwondo under Professional Karate Association superlight champion Gordon Franks, and he loved it and started competing in tournaments when he was only a gold belt, a beginner’s level. Unfortunately, when you’re a gold belt, they didn’t let you kick or punch your opponent’s head. Because of this, he didn’t really get excited until he was a green belt where this was lifted. During his training, he would work out five or six hours a day and competed in tournaments all over the country. There was no money involved but a lot of partying.

In 1978, he took a job as an instructor but was only getting $600 a month and was spending $400 on tournaments. Eventually, he would become a black belt and would meet his friend in a match, Randy Reid, at a tournament in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Bischoff actually beat the shit out of him and bloodied him like crazy but lost due to “excessive contact”, “which was better than winning a trophy, as far as I was concerned”. That night, the two partied together anyway. By 1981, Bischoff gave up martial arts because there was no money in it, and he didn’t want to be an instructor. Instead, he pivoted to sales and worked as a salesman for Blue Ribbon Foods who made and delivered bulk frozen food to individual homes. Most of the work was in the early evening, so most of his day was free. Irv Mann hired Bischoff who refers to himself as one of the only “non-Jews” Irv hired up to that time. He was also one of the few under the age of 50. Irv taught him how to structure a pitch, read a potential sale, how to overcome projections, when to close, and when not to close. Bischoff says the film Tin Men was an accurate portrayal of the aggressive style of direct sales back then. Bischoff became one of the better salespeople in the company by 1982, closing 30% to 40% of his calls. While he was working at Blue Ribbon Foods, someone suggested he would be a good male model. He never thought about it before, but it was a day job. Since he only really worked sales in the evening, he could do both. Within a few weeks after getting set up with a modeling agency, he started getting jobs for places like Target and it paid well. Plus, it led him to his wife, Loree. She was not only a model but part owner of an agency he was working with. There was an initial hurdle of the “no fraternization” policy, but that didn’t stop things from progressing. Lorre was a model since the age of four or five and was trying to make a career of it. Since there was nothing to hold them back, they decided to move to Chicago to a studio apartment downtown to make the dream happen.

To earn a little money in the meantime, she worked as a cocktail waitress at night in hopes of launching her modeling career in the day, and Bischoff worked as a bartender and doorman at night in hopes of doing the same. After a year though, they realized it wasn’t happening. It got to the point where the power company shut off everything in their apartment just after Christmas. Cutting their losses, he moved to Braham, Minnesota, as Bischoff accepted a sales job from an acquaintance of his dad who ran a company that made agriculture equipment called Dahlman Manufacturing. For the first few months, he lived alone while Loree finished up the last of her modeling gigs. It was lonely, cold, and dark, but he was decent at the job. It was enough to make ends meet, and it could transition to a better job for him. In the summer of 1983, he picked up Loree back in Chicago and headed back to Braham with her. Soon after them settling in, they found out Loree was pregnant. He never thought about marriage or a family at that point, but the news changed everything. Not knowing what the other was thinking, they both said at the same time they wanted to have the baby. Right there, Bischoff realized things needed to change in terms of his career. At the time, they still weren’t making much money but would still find ways to have fun. On Sunday mornings, they would have a nice little brunch and would typically watch Verne Gagne’s AWA wrestling. Loree wasn’t really into it. She never deterred Bischoff from watching, but she wondered why he watched it. He explained to her that “in my mind, wrestling is the purest form of entertainment, and therefore the purest form of marketing that there is”. He loved it and often pondered why others liked it to try and understand why it was successful. Unbeknownst to him, Vince McMahon was revolutionizing the business in the 1980s, using cable to deliver a national program. Until then, regional promoters like Verne and Vince McMahon Sr. made local television deals and stayed out of each other’s territories. It was a gentleman’s agreement for all of the territories.

Of course, we all know that Vince McMahon Jr. didn’t give a fuck about any of that and syndicated his show across the country.

As this was going on, Bischoff and Loree spend a year or a year and a half in Braham and their first son Garett was born on April 20th, 1984. Right after, they moved to Minneapolis and rented a house near Loree’s parents. Bischoff went back to Blue Ribbon Foods as a sales manager, managing a sales force of fifteen people. His daughter Montanna was born in November 1985, and Bischoff and Loree were married by then. He admits Montanna’s arrival was also unplanned, but they were looking forward to having another. Though Bischoff was developing a great relationship again with his boss Irv Mann and enjoying life, close friend Sonny Onoo came to Bischoff with an idea for a kids’ game, Ninja-Star Wars. Bischoff and Sonny met in Bischoff’s martial arts days. Sonny was born in Tokyo but found himself in Mason City, Iowa somehow. He owned a couple of karate schools, was a top amateur martial arts competitor, and became a professional kickboxer in the 1970s. One night, the two were drinking at a bar and started talking about games they used to play as kids. Sonny talked about one called “Ninja”. He and his friends would take milk bottle caps or whatever they found and threw them at each other like five-pointed martial arts stars. With this, he invented a game based on this game he played as a kid, and they called it Ninja-Star Wars. They were convinced of the games success and put all the money they had into manufacturing the game. They found a manufacturer in Korea who would make the games for them and put them in boxes and everything, “but the economy of scale required meant our initial order was something like ten thousand games”. They didn’t have a warehouse to store them either. They were all over his house. Bischoff and Sonny spent a couple of months trying to take them to retailers to try and get them on shelves, but this is when they learned about the realities of the toy business.

So, “stores allocate square footage to toys based on the distributor’s success in the marketplace. If you’re Mattel, you might get 60% of the shelf space. If you’re Hasbro, you might get 30 percent. If you’re Joe Blow’s toys, you get whatever’s left. And anyone else – Eric Bischoff and Sonny Onoo, for example – doesn’t get squat”.

To try and create some buzz, Bischoff and Loree would stand in front of independent toy stores playing the game and would tell incoming customers about it when they asked. The stores wouldn’t inventory the game, but they would sell them that day while they were there, so they did so every Saturday. Still, the process of moving the inventory was taking a long time. In between appointments at Blue Ribbon, Bischoff stopped at home and saw AWA’s show on ESPN and there were some “per inquiry spots, which are direct-response sales. A number flashes on the screen, you call it and get the advertised item”. Seeing the ads during the show, Bischoff saw the opportunity. A lot of kids watch the AWA, so this might be a great way to sell off Ninja-Star Wars. Knowing he could get an appointment with Verne if he brought up his amateur wrestling background, he knew he could close a potential deal with him if he got in the door. He managed to get a hold of Verne through the phone after bringing up his wrestling background and reminded him of the first time he met Verne and how he wants to run an idea by him. Without question, Verne accepted and invited him over the next day. He went to the AWA office and went into a meeting room with a massive table and people like Verne, Greg Gagne, Wahoo McDaniel, Ray Stevens, a couple of secretaries, the accountant, and everyone else in the office present to hear his presentation. He put on the equipment of the toy and started throwing his ninja stars around and Verne was enjoying it. Bischoff said that he would cover the cost of the commercial out of his own pocket, and Verne could run the commercial on his show. The games cost Bischoff $8.45 each, so he’ll sell them for $20 and him and Verne will split the profit 50-50. Thankfully, he accepted. Within a month, they were selling games on ESPN. After all of this, they were relatively successful, but it wasn’t enough to pursue it further, so Bischoff and Sonny pulled the plug. By this time, Bischoff became familiar with the Gagnes and Mike Shields.

Mike had come up with Jerry Jarrett and did everything from running cameras to helping with booking. He “handled advertising and syndication for Verne, heading up the production department”. Bischoff developed a good working relationship with Mike, and he would ask Mike a lot of questions to get a better understanding of all the things he was involved in like syndication and such. Eventually, Mike offered him a sales job with the AWA, and he accepted. His first day was August 15, 1987. Because the office was in a small building that used to be a church, Bischoff was forced to build his own little cubicle with two-by-fours and Sheetrock. One day, Sheik Adnan El Kaissey and Nailz got into a real fight backstage and Nailz sent Sheik’s head though the Sheetrock beneath one of the photos on Bischoff’s wall. In Chapter Two (“Ken Doll”), Bischoff wants to clear up the bullshit that has been said about his time in the AWA. He never took a job mowing Verne Gagne’s lawn, he was never the “architect” behind the horribly executed Team Challenge Series, he never booked for the AWA, he never clashed with Verne over wrestling styles, and he was never a general manager. During his time in the AWA, he had zero input on anything that happened onscreen. His role was primarily in sales and marketing. The only time he would see the wrestlers was once or twice a month when they came in to shoot promos. Verne was very strict about kayfabe and didn’t want anyone knowing about the inner workings of the business other than those who need to know. Even if Bischoff walked out of his office and near the studio, and Verne was talking to a wrestler, he’d whisper in the wrestler’s ear so Bischoff couldn’t hear anything. For a year and a half, all Bischoff did was syndication and sales. Though he was making only $30,000 a year, which was less than what he was making at Blue Ribbon, “it was regular” and he loved it.

The AWA had two main components, live events or promotions in different locations and television shows. Their live event business was driven by local television markets. The more television stations or local markets that carried his show, the better the live event side of his business did. The TV shows gave them an opportunity to promote the events. This was the best way of advertising the shows. Bischoff’s job was to increase the number of stations syndicating the show. This way, it could expand Verne’s live event territory. It would also help them increase advertising revenue. Within six months or so, Bischoff took the AWA from 32 stations to 65 or 70. About a year in, Mike Shields invited Bischoff to Las Vegas to sit in on one of their shows to “watch what we do”. Along with everything else he did, Mike directed the ESPN show that Verne shot in Vegas at “a small off-strip casino called the Showboat once or twice a month”, so he gave Bischoff the job of technical director. With this, Bischoff was given his first foray into producing television and he was eager for the career progression, fascinated with how it all worked. Then, in 1988 or 1989, the wrestling industry world get their first taste of Eric Bischoff as an on-camera talent. He never asked for it and was happy and sales in marketing, but it fell in his lap because of the need for an interviewer. With this, Eric Bischoff found his first stop on the path to becoming an iconic figure in professional wrestling and key figure in transforming the business.

Of course, until it all came crashing down…

My Thoughts:

Eric Bischoff is a polarizing figure within the professional wrestling industry but an undeniable legend no matter what way people want to slice it. Some give him too much credit, some give him too little of credit, and some look for any possible angle to criticize his decision-making when he was running World Championship Wrestling while doing so with the benefit of hindsight. Though Bischoff can come off as a bit smug about things, especially now, anyone who takes the time to read Controversy Creates Cash will see things much differently than how the media has portrayed them to be. Now, it seems Bischoff’s demeanor in the present day seems to be more of a defense mechanism if anything, as it has been created as a response to those who trash his legacy. With a book like this and how he reacts to criticism, it’s Eric fighting back and I can’t say I blame him. The amount of flack Bischoff has received from people who have never worked in television or professional wrestling would make any sane man crumble and lash out, but Bischoff has responded with factual information in an entertaining fashion while appreciating his journey and the legacy he has created. Wrestling pundits and fans call him an outsider of the business and how he’s not a “wrestling guy” because he didn’t work in the territories, but Bischoff worked for the AWA and led WCW to its only profitable years in existence before working for WWE and TNA. Not bad for someone who was supposedly some “Hollywood dreamer” who fell into wrestling, a claim Bischoff denigrates quite early. Controversy Creates Cash details the start of Eric Bischoff’s life through the entire run of WCW to his beginnings in WWE as a full-time onscreen character. What makes it a must-read for any professional wrestling fan is that it explains everything that happens behind the scenes from someone who was actually there and making the decisions.

This sounds simple, but it’s quite important to note.

As wrestling fans know, Bischoff was always looked at as an outsider of the business, something he isn’t shy about in his book. The dirtsheets and internet wrestling community have never given him the benefit of the doubt because he wasn’t a “wrestling guy” and didn’t grow up in the business. No matter what he did, especially when he was helping take wrestling to heights it has never seen before, people would badmouth any decision he made and talk shit about virtually everything he did. It’s gotten to the point where they refuse to acknowledge his contributions to the wrestling business, and that is a travesty. Everyone knows about the fall of WCW, and everyone likes to point fingers as to who is responsible, as if it’s a simple answer. When looking at all the factors and analyzing what went down, you’ll realize that there were a lot of contributing factors that forced a downward trajectory, a trajectory that would have happened with or without Bischoff. Eric Bischoff may have been one of the faces of WCW, but looking at him being the problem is exactly what the executives behind the scenes want people to think to avoid the shame of the public. This book is written as a response to all of the bullshit criticism Bischoff has faced, and he paints a clear, step-by-step picture as to why things happened the way they did in WCW and why it was destined to fail. It’s perfectly executed, honest (at least from his perspective as a reasonable executive and reliable narrator), and there are no questions left unanswered, barring the more fun topics of creative decisions depicted onscreen. Honestly, it’s so well done that if every wrestling fan read Controversy Creates Cash, Bischoff wouldn’t need any podcasts, documentaries, or further interviews at random conventions to explain things. It’s all right here in print. For those who can’t get enough of the Monday Night Wars, the glory days of wrestling, and WCW, you have to read this book.

Recently, Vice TV did yet another miniseries over the subject with Who Killed WCW?. If you’ve read this detailed autobiography however, you’d realize how unnecessary that series was. Plus, it goes into even less detail than Bischoff does for the reader here. It doesn’t even compare. After going through countless hours of research within interviews, books, TV specials, articles, and firsthand and secondhand accounts, I have come to the controversial decision that many basement-dwelling fans may dislike: Bischoff was right.

The only people who disagree with him are (1) people that didn’t work for WCW, (2) wrestlers that had zero clue about the uphill battle he faced with executives during Turner Broadcasting’s merger with Time Warner and the subsequent merger with AOL, and (3) the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, a publication he’s at war with to this day and who also have zero experience in television. Once the mergers began, the risks and entrepreneurial spirit that existed within Turner Broadcasting when he started were gone and Bischoff’s biggest supporter in Ted Turner was neutralized. Look no further than the end of Chapter Eight (“Too Much; Bret Hart & The Montreal Screwjob”), as he met with Turner Broadcasting executives following his angle with Jay Leno. Terri Tingle of standards and practices deemed Leno’s jokes as no longer appropriate, which he chalks up to Time Warner being filled with Democrats and Leno making fun of Bill Clinton. With this, she demanded all the “scripts” for Eric’s shows 2-3 weeks in advance so she could review them before airing them, not knowing that this isn’t how wrestling was done back then. Bischoff was basically cornered by a room full of executives that had no idea how he conducted business, how wrestling was done at that time, and didn’t even watch the show. He had to explain they only have outlines and formats, with bullet points and production directions, but things were just getting started. Eric took them all one by one and shot down each idea, thinking that he still had the Ted Turner card in his back pocket, which he later found out wasn’t worth what he thought it was after merger and Ted lost control of his own company. In the same meeting, an executive Bischoff decides to keep nameless basically tells him that they are repositioning WCW in the advertising community, which WCW had no control over because it was all handled by Turner’s advertising department, giving them the gall to tell Eric how to run his show. The new direction the exec wanted was for WCW to go back to being targeted towards children and families. This is when people need to acknowledge as the beginning of the Titanic sinking.

Bischoff saved the company in the first place by changing the focus of the show to the key demographic of 18-39 males and going after realism, unpredictability, and edgy content. This is what set it apart from WWE’s programming and made WCW the cool and badass product that killed WWE in the ratings for as long as it did. It forced WWE to usher in the Attitude Era. At this point in time, WCW started getting real competition from their opponents across the pond because of how much they were pushing past the benchmark WCW laid down. Instead of responding in Eric’s usual hyperaggressive way and going back and forth with what could have been even MORE neck and neck than ever before, he was met with pushbacks from executives that didn’t watch the show and wanted to do the EXACT OPPOSITE thing that got them to the dance in the first place! It’s there when Eric knew he was losing control of his own show after finally making it a success and considered quitting, but he couldn’t because it’s in his nature to fight, a theme routinely present in this autobiography. On top of that, he had a contract and there was nothing in it that allowed him to quit by just not liking the working conditions. Not leaving after that meeting became his single biggest regret though. I’ll give Eric credit. Him asking the nameless executive what night of the week Nitro airs to prove his point about how they don’t know what they are talking about has to be one of the most badass things to ever happen in corporate America at that time. He knew it wasn’t going to help him in terms of politics, but he had to make a point and was proven right as the guy had no clue. Regardless, the restructuring after the merger was detrimental to WCW’s trajectory. All the people in positions in Turner Broadcasting who never liked or supported WCW were calling the shots and making decisions for all the divisions in the company. In addition, the new powers wanted “corporate clones and not mavericks”. Bischoff’s “maverick” style worked with the old regime, as his outside-the-box thinking fit with Ted Turner’s willingness to take risks to succeed, but he was handcuffed when WCW needed him most as the WWE’s Attitude Era started to take off.

The company was built on Ted Turner’s mantra of taking chances and having vision, but it was flipped upside down, and WWE lucked out because of it. They won’t tell you this in those revisionist history WWE-produced documentaries. Plain and simple, just when things could have started getting interesting in 1998 and 1999 with both companies being at their height, it turned into an unfair beatdown that WWE benefitted from without trying! Bischoff points out how Gerald Levin claimed he wanted “to merge with Turner to inculcate Time Warner with the Turner entrepreneurial culture”, but it worked the other way around because those people who had a creative vision became “paralyzed by fear or their own greed and concern for stock options”.

“The atmosphere became one of paralysis. Decisions weren’t made, boats weren’t rocked. Standard operating procedure was to form a committee to name a committee that would appoint a group to study the problem, then report back to an advisory committee to make a presentation to the original committee. It was like working for the federal government”.

Eric reminds the reader how on Raw, they had Sable with her tits out and Mae Young birthing a hand, but Terri Tingle of standards and practices told him that there are things that WCW isn’t allowed to do that aren’t on the list she made for him. So, “If you want to do anything we might be offended by, you have to call us up”. Do you see how ridiculous this is? Do you see how screwed Bischoff was? It’s like being in a boxing match with a professional and having both hands tied behind your back! WWE had no restrictions at this point to try and beat WCW, and WCW ran into a brick wall that was this corporate merger who gave them a list of things they couldn’t do anymore, even though it helped them become a success in the first place. At the same time, they were limiting their budget and shooting every idea imaginable that Bischoff had to save the place. Finance took a look at Thunder and slashed their production budget because they wanted to reach 20% growth in all their divisions. In doing so, they had to cut costs. This hit the promotional budget, so Eric couldn’t even market the show, one that he didn’t want to have in the first fucking place but agreed to because of Ted Turner’s insistence! It’s not for lack of trying either. Even when he was at his most miserable and purposely had attitude to anyone who tried go against what he was doing, Bischoff still put on a brave face for the others within WCW because he didn’t want to ruin their morale as much as his was. He knew the death nail was going back to family-friendly programming, among other things in 1998, but he lied to everyone and said it was the right move to try and be a leader and company guy. Behind the scenes, he was still fighting though, and it’s hard not to commend him for his efforts. There are a lot of interesting sections about said efforts like the NBA lockout allowing for some holes in NBC’s programming, so Eric came up with the idea for prime-time special St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, which would end with Dennis Rodman and Carmen Electra getting a divorce in the middle of the ring. NBC greenlit it, so he took it to Harvey Schiller. Since Harvey wasn’t allowed to make the decision anymore, he took it to the Turner executives, and they turned it down because they felt that putting their brand on NBC would put Turner salespeople at a disadvantage.

They didn’t even call him when they made the decision too, and it forced him to put the NBC people on hold until he found out, which ruined that relationship. Eric remarks how this still pisses him off to this day, and how can you not agree with him? This is the type of detail that no other WCW-related DVD or interview has talked about before or since but is crucial in explaining how Turner/Time Warner didn’t want WCW to succeed and did “everything they could to lay groundwork for WCW’s failure so they could get it off the books”. The proof is in the pudding. The same could be said going into the millennium. They were projected to lose $1 million as a company to finish out the year, so Bischoff still came up with an idea on how to fix it, New Year’s Evil. It would be a WCW PPV that would end at midnight and would include a KISS concert, potentially delivering $3-5 million to the bottom line when they needed the revenue. He worked out the logistics with the Fiesta Bowl, but people at WCW were afraid of the world ending and killed the idea. Guys, I’m not kidding. This is the type of shit they don’t talk about. Eric points out how if this was two or three years earlier, he wouldn’t have even sent a memo before going through with the decision, but the merger was that devasting to Bischoff’s success as an executive.

“We’d come up with a solution, everything was in place, and I was told no”.

I respect the hell out of Eric for going out of his way to tell the committees that killed the idea that their decision guaranteed WCW was going to lose money that year and how if they ask why they are in the red, he’ll remind them of this PPV. You can’t cut everything the guy has and shoot down every idea and then demand he makes money. It’s as simple as that. After trying to work with the head of the financial division in Vicki Miller and explaining pretty much how once they’ve lost the audience in wrestling, they can’t course correct and she had zero response, he was done for.

Also, for those that think they have the answer to the financials, Eric also makes it clear that “No facts written about WCW’s losses had firsthand knowledge of the situation”. So, he lets us in on some crucial details. Even though Time Warner was a public company, WCW’s finances were not made public because their revenues and expenses fell into a category referred to as “other income/losses” on the Turner and Time Warner balance sheets. Other divisions were reported this way as well and it gave the accountants the ability to shift some of the figures from the others around. This allowed their “accounting division to forecast losses in such a way that could be estimated (some cases overestimated) and included in a forecast that might benefit the division or department in any number of different ways”. Of course, “intercompany allocations and forecasts were used and abused to help various divisions or departments position themselves internally for future budget considerations”. In August of 1999, WCW was projecting a loss of $1.5 million, but the media reported it as much higher. When Eric saw the numbers months later, it basically showed that management had decided to dump as much of a projected loss on the books as possible for fiscal 1999. This way, management could look as good as possible in 2000, but WCW looked awful. Now, tell me geniuses…

Was the problem that Eric gave Hulk Hogan creative control, or was the political and financial maneuvering stemming from the executive chairs a little too much to overcome once he lost the audience, which was also due to his inability to fight back because of the executives? It seems like a pretty simple answer to me. WCW almost put WWE into bankruptcy and when it got close, they essentially were told to stop everything they were doing. Once they started losing the war with the politics and to the WWE, the downward spiral couldn’t be fixed. Everything was done by committee at this point, and the committee didn’t like wrestling. This includes the rebranding of WCW led by VP of marketing Jay Hassman. None of WCW’s creative people had a hand in designing anything, and it became infamously terrible. Scott Hall started messing with Brad Siegel’s daughter to basically save his job after Bischoff noted how Hall was “unmanageable” at that point, 1998’s Halloween Havoc ran fifteen minutes over and the feed was cut on PPV forcing them to give away the ending for free on Nitro, which made everyone look stupid, WCW’s headquarters were moved away from CNN Towers and rest of Turner and into a warehouse in Atlanta after the corporation bought an NHL team to take their spot, which made everyone in the company feel like the redheaded stepchild of Turner again, and the already disgruntled Bret Hart lost his passion completely after his brother Owen died, and he was one of WCW’s most important signings. As a wrestling fan, it’s kind of funny to see how Eric wishes the best for Bret and hopes for him to be able to get over some of the real-life feuds he had with some wrestlers, even saying they could get a beer someday, because Bret still trashes Bischoff to this very day, along with WCW as a whole. On top of all that, Goldberg wanted to renegotiate his contract, despite having a year and a half left on his deal. This led to Bischoff having to deal with dickhole Barry Bloom and Hogan’s asshole attorney Henry Holmes (who Eric correctly guesses would bring up the George Foreman grill deal when they had their meeting, which got a laugh from the executives present).

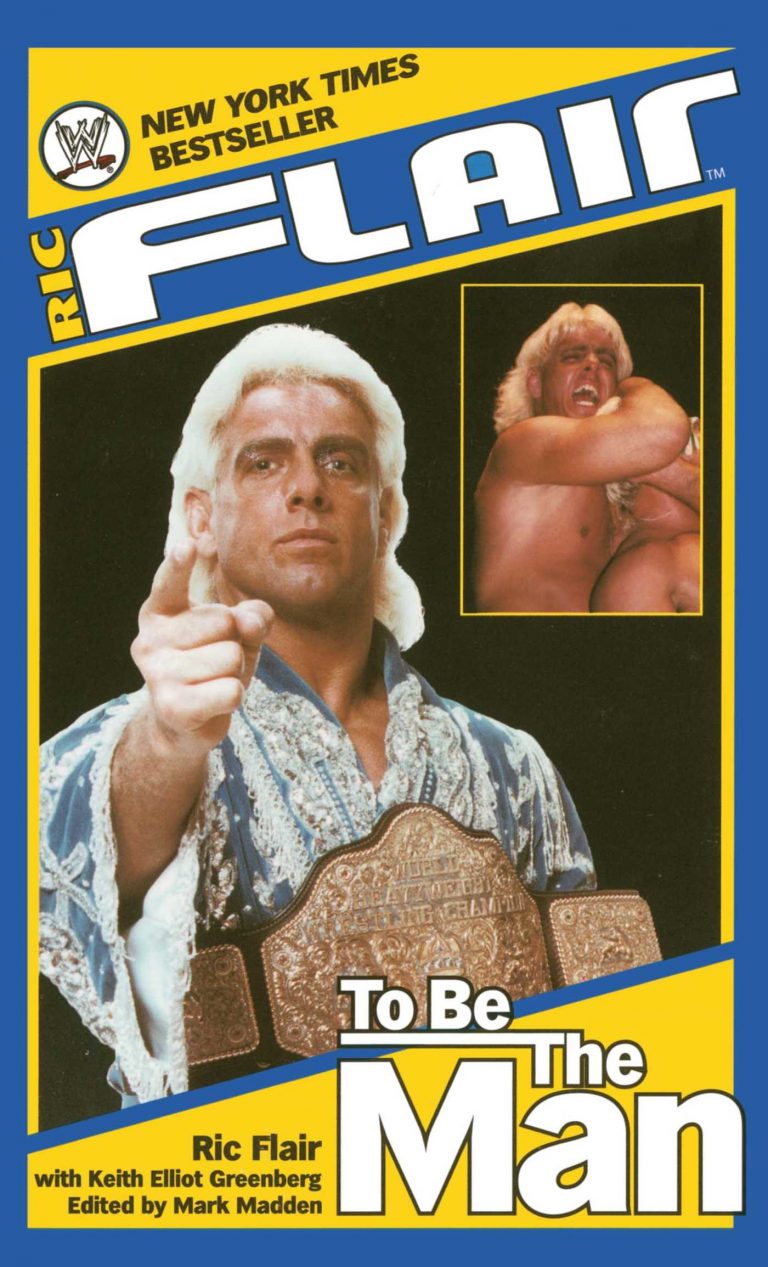

Eric wanted to take the stance he did with Ric Flair, and he had every right to, but they created the monster in Goldberg and were relying on him heavily and couldn’t afford to keep him on the sidelines. So, they had to give him everything. They fucked Eric so badly, he came out respecting and befriending Holmes and Holmes represented Eric in his deal with WWE! Regardless, imagine dealing with all of this while going at war with the executives who are doing everything in their power to kill the company. Not long after, Bischoff unravels and threatens to quit privately to Bill Busch. Busch wanted his job and got it after snitching to Harvey Schiller who sent Eric home. He couldn’t fire Eric because he had two and a half years on his contract, but this ended his run as the lead man in charge, yet another decision that led to WCW’s death. Still, following the failed Vince Russo experiment that resulted in Bischoff just stepping aside because of the lawsuit Russo put the company in after his shoot on Hulk Hogan at 2000’s Bash at the Beach, Bischoff offered to buy WCW outright. Pay attention kids, this is why WCW died more than anything else. Partnering with Briant Bedol of Fusient Media Ventures, Peter Gruber at Mandalay Entertainment, and some other venture capital companies, they put together a package worth $67 million with Bischoff handling the TV and wrestling side of things and Brian handling the business side. Bischoff’s elaborate plan was to shut down the company to give it a sense of being reborn in the eyes of the fans, and it would allow them to rebuild it creatively and have a grand reopening when the time was right. The live event business would be shut down, and they would build a small arena at the Hard Rock Cafe in Las Vegas, filming all their shows there to save on production costs.

Not bad, right?

Well, WWE came into play, so Bischoff and company had to revise their initial offer, which gave Brad Siegel an opportunity to pursue WWE’s inquiries. So, they backed out since Siegel shopped WCW without trying to renegotiate the offer. Viacom made Vince McMahon back out of the deal because they wouldn’t let him buy WCW and air his show on a rival network. Following this, Siegel asked Eric to put the deal back together, which didn’t go over well with Fusient because they “weren’t convinced Brad and AOL Time Warner were operating in good faith”. Even so, they renegotiated, and the deal was officially announced in January with a signed letter of intent. Eric and Brian met with employees, they held a press conference and had a call with Wall Street. It was done. They even spent the next month or two working out legal and business details involving the sale. After all of this, Eric gets a call on his vacation in Hawaii that the deal was somehow off the table. Yes, “Jamie Kellner killed the deal”. Jamie Kellner took over TBS and TNT and looked at all the pending deals. The acquisition from Eric’s group included copyrights, trademarks, assets, and most importantly a “10-year broadcast window at TBS”. It still ensured them four hours a week for both Nitro and Thunder, and they controlled the inventory, which meant “they got the revenues from the commercials during that time”. Kellner didn’t mind selling WCW, but it came back to the problem that was a thorn in Bischoff’s side from the very beginning: He was another exec that didn’t want wrestling on his networks. Kellner took the distribution element out of the agreement and eliminated the broadcast window, effectively cutting the value of the deal to pennies. After a last-ditch effort for a commitment from FX, the deal was dead in the water. Shortly following this, Vince McMahon swooped in because Viacom no longer had objections since broadcasting wasn’t part of the deal anymore. Had Bischoff secured this deal like it was agreed upon, it’s likely the company would have survived to this very day, similar to how TNA still manages to scrape by.

There you go… That is what killed WCW. It was all of these factors and more, but make no mistake about it, Bischoff still would have saved it if it wasn’t for Jamie Kellner bludgeoning this deal with a sledgehammer after the terms were already agreed upon.

We can talk about creative decisions all we want as fans and how it led to WCW’s demise, but Controversy Creates Cash explains the nitty-gritty, less talked about details that aren’t spotlighted like they should be. The corporate bullshit Eric had to fight CONSTANTLY to try and make WCW succeed is what killed the second biggest wrestling company of all time. It’s not as eye-popping or as easy to talk about as Vince Russo, the botched finish of 1997’s Starrcade, or the misuse of Bret Hart. The experts like to point out WCW’s use of guaranteed contracts and why it contributed as well, but not only were they doing this before Bischoff took charge, it was the only bargaining chip they had when the company wasn’t doing anything in the business of licensing and marketing. WWE were huge in this, which is why they didn’t have to guarantee money. The talent was just paid whatever Vince McMahon felt. They wanted to get to revenue sharing lines for their compensation plan, but they weren’t there yet. Even so, there’s so much more to it than that. WCW could have survived had they had the support from executives, and they appreciated the work and success Bischoff pulled off as president. Unfortunately, besides Ted Turner himself, Bischoff had very little backing from the important people in charge and it needs to be talked about much more than it does. Fuck all the talk about “the nWo storyline went on too long”. No, let’s talk about the general practice of Turner Broadcasting in that, “Often, Turner Broadcasting would find an executive who, for one reason or another, wasn’t working out in the division or department he was in. Inevitably he would be earmarked to be the next WCW president”. Basically, they got the worst guy available. Since they were already the redheaded stepchild of the network, they would get people like Kip Frye, who was an attorney in the entertainment division and had zero experience as an executive and knew nothing about wrestling. Considering he followed Jim Herd, this should give you a good idea on how things were happening before Bischoff started climbing the ladder.

One thing Bischoff does make sense of is that it’s not the worst idea to give an outsider this type of job just because WCW was run at that point by wrestling people for many years and business was a lot worse. It consisted of former wrestlers turned bookers who worked for the Crocketts in the NWA and stayed on after the sale to Turner. When you buy a company and bring everyone associated with it, odds are that you’re bringing over a lot of the cancer. Plus, most of them “couldn’t adjust to changing times”. Argue all you want, but Bischoff is sadly correct about this. They needed television people to advance the product, not territory guys who thought in archaic ways like Bill Watts. On top of that, the politics within the company who weren’t executives were just as bad. Eric suggests that anyone who had some sort of political stroke had a self-serving interest and names Jim Ross, Tony Schiavone, Dusty Rhodes, and VP of PPV and marketing Sharon Sidellos as those with their own agendas. It’s just like any workplace, and all the department heads at WCW had their own agendas and were “politically aligned in different camps”. That was one thing Eric would have changed when he was close to buying WCW in 2001 with Brian Bedol. It was hilarious to hear his brutal honesty about his late return to look at the staff. After referring to Bill Banks as “the most underwhelming person I’ve ever met, creatively speaking”, which is an insult I will definitely use in the future, he talks about the rest of the “unqualified misfits” left over, along with his shock that somehow Sharon Sidello and ass-kissing politician Gary Juster (“The most ineffective, untalented individual I’ve ever had the misfortune to work with”) were still there. Learning from his mistakes before, Bischoff tells Brian to get rid of all of them and to start from scratch, and the experienced Brian agreed once he met all of them. This is one of the important lessons Bischoff learned saying, “It’s often better to start from scratch rather than trying to work with people who were part of the problem in the first place”. It’s pretty hard to argue with this after reading what he went through and should tell you a lot about the state behind the scenes when he signed on.

It’s all just the tip of the iceberg in the problems Bischoff faced, as it only increased when he rose in power.

Another thing that no one talks about is that a lot of the people who produced the shows weren’t WCW employees and didn’t understand wrestling. They were Turner crew members who did everything TBS did like Atlanta Hawks or Braves games. Since WCW was treated as a last priority, they would never get the best workers available because those crew members would go to the bigger shows and sports. WCW got people who were transferred around based on the needs of the company. Some may have been good at filming other sports, but they didn’t know how to film wrestling, which explains a lot. It wasn’t a big deal when they weren’t doing that well, but the problem was magnified once Bischoff made WCW a big deal in prime time to where they were getting 30,000 people in the audience a night. When he took over, he didn’t have the budget to hire great personnel, so he dealt with what he had. Then, when they got bigger, the issues were noticeable, but nothing was done because they were making so much money at the time. Along with this, there were a lot of people who needed to be fired that were “unqualified for the positions they were in” like the aforementioned Gary Juster and Sharon Sidello who “didn’t have the vision to grow her department to the extent she should have grown it”. Wait, that’s not all! When things were at their peak and the “increased revenue would have justified a larger payroll”, there was a companywide hiring freeze, so Eric could only take someone from inside the company. Of course, the only people who were available inside the bubble were “earmarked for termination or requested to be transferred to another division”! He couldn’t steal people from other departments either, leaving Bischoff’s options to people who “had to be thinking of quitting or about to get fired”. If they fit into these categories, HR would send them his way. This was when WCW was already operating at 110% capacity. How the fuck was Bischoff supposed to respond if this was the only help that he could get to manage their success?

On top of all of this, Ted Turner wanted WCW Thunder to be made, another two hour show on prime time, but the kicker is that Eric was given zero dollars to pull it off! The idea came in the midst of higher-ups from the merger focusing on increasing profits in the short run by cutting expenses via EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization). Because of this, no one wanted to do anything that would increase their division’s expenses, like contributing to a new wrestling show, since they wanted their profit centers to have good numbers (their stock options depended on it), but that was exactly what Bischoff was tasked in doing. If he were to have another Nitro-like show, he would need 40-50 more people with “15-20 production people alone”. Bischoff deduced it would cost around $12-15 million, and TBS refused to pay it. How can you not say Bischoff was screwed here at his peak? He does reveal that he could have declined, but he didn’t think he was in a position to argue with Ted Turner and wasn’t given an opportunity to discuss or vote on Ted’s decision. Many of us in the corporate field can relate to this, and I feel that not a lot of people understand why this is a logical response by Bischoff. Despite being undermanned and knowing this is a bad idea, he went through with the daring venture because he just wasn’t in a position where he could take on the guy who gave him the opportunity in the first place. At the same time, Eric didn’t want to disappoint the guy who gave him a chance and he was overconfident. It is what it is. He still found a way to make it happen and made Thunder a success, but it was just part of the downward slope because of how fast they were moving and how underprepared they were for it.

Make no mistake about it, Bischoff admits his faults more than you would expect in this book (like with the poor handling of Arn Anderson’s retirement) but a lot of the time, he justifies his decisions well. He wanted WCW to succeed and wasn’t afraid to ruffle the feathers of traditionalists, which is why he wanted to film the show at Disney/MGM Studios. He makes a good point in saying that hardcore wrestling fans hated the move, but “but there weren’t enough of them to support the brand, and I wasn’t going to cater to them”. It’s about bringing in the casuals! Fans of All Elite Wrestling still don’t get it, and Bischoff has been proving why his thought process works for literal decades. He admits he shouldn’t have disregarded the traditions of the old NWA/WCW as much as he did, but he brings up a valid point. If those traditions were that important to everyone, they wouldn’t be a consistent financial mess in the first place. Everyone trashed him for wanting to cut live events while instead focusing on producing TV and dumping the rest of the resources in acquiring talent and dressing up the product, but he was 110% correct, as these are the key moves that made them an eventual powerhouse. It’s hard to argue with the fact that they didn’t have a single profitable year before or after Bischoff. Sometimes, traditions need to be thrown to the side. Nobody wants to admit it, but the best decision ever made by WCW was to look for a television guy who understood wrestling but wasn’t a “wrestling guy” stuck in the old school mentality. It was the only way the business could proceed, and Bischoff was the right man to lead the charge. In Chapter Six (“Prime Time; He’ll Understand”), he explains a lot of his decisions early on that he routinely gets criticized for but his way of explaining the thought process of each one makes total sense from an outsider’s perspective. For instance, the way he handled the Jesse Ventura situation was completely justified. We know he had his issues with Hulk Hogan, but the fact of the matter is Hogan was/is the biggest draw in the history of wrestling if we’re talking modern era (Shout out to Jim Londos).

For Ventura, who was being paid half a million to just be a fucking color commentator, to act like a miserable asshole to everyone at the time is outrageous! According to Bischoff, who gave him a lot longer leash than he should have just because of Ventura’s star power and contract, Ventura had started to pout like a child, had a bad attitude, was treating people badly, would show up late, and behave like a “spoiled brat”. All of these reasons alone would be enough to finally cut ties, but Bischoff dealt with it. The final straw came in 1994 when Ventura didn’t show up on time for a taping, and Bischoff found him in his dressing room asleep. Then, Ventura had the audacity to start bitching again when Bischoff woke him up. How is Eric in the wrong here? I like Jesse Ventura as much as the next guy, but this is completely unprofessional behavior for someone WHO IS A COLOR COMMENTATOR! They’re already overpaying him for a position that is expendable no matter how big his star power is, and he was that awful behind the scenes? He wasn’t worth it, especially if he was going to cause problems when Hulk Hogan was on his way to the company. Tell me, would you take the side of a color commentator over the wrestler who might be the biggest attraction in the industry at the time? Of course not! If you would just because you’re not a Hogan fan, there’s a reason why you aren’t a television executive. For the record, Bischoff didn’t even fire Ventura. He just stopped using him and let his contract run out because he was that much of a “cancer”. I understand. In a dream scenario, it would have been awesome to have Ventura a part of WCW in its prime years, but it’s just not that simple. Don’t blame Eric Bischoff for it not happening! This was on Ventura completely, and Bischoff had to respond like an executive producer. Sometimes, you have to make the hard decisions, and this was one of them. Then again, Ventura made it easy if he really was like this at that time in his life.

Another controversial decision was letting go Steve Austin. Everyone brings up hindsight and they trash Bischoff because getting rid of Austin backfired, but I can’t help but agree with Bischoff once he explains the circumstances surrounding it. First of all, Austin’s idea to be a relative of Hogan’s, so he can work with him when he came in was dogshit. Bischoff told him he’d think about it, but he never had any intention of going through with it. Plus, Hogan wanted his first program to be with Ric Flair, which was obviously the way to go to get WCW some big fanfare. Could they have revisited a Hogan/Austin storyline? It’s possible, but it wouldn’t have gone anywhere at that time because Austin wasn’t the star he would become. He was a completely different wrestler at that time. On top of that, Bischoff details how Austin was injured, started to get a bad attitude after this, and was dealing with personal issues, and it all came at the same time of his negotiations for a new contract. After he no-showed an onscreen interview, Tony Schiavone called Austin’s home, and his wife said she didn’t know where Austin was at. The kicker is that Austin could be heard in the back saying, “Tell that son of a bitch I’m not home” and to say she didn’t know where he was at. Schiavone relayed this back to Eric, so he fired Austin as a response. Knowing all of this, would you have fired him? I sure as hell would have! It’s not only unprofessional but disrespectful as hell, especially for an injured midcarder with a bad attitude. Bischoff acknowledges that he has been criticized for not firing Austin in person and did so through the mail, but he states that he didn’t feel like he owed Austin any other type of response. Considering Austin’s antics throughout the negotiation process, I 100% agree with Bischoff here. Why should he respectfully let him go in person when Austin said all that behind his back in the most disrespectful way possible?. Bischoff admits that it backfired, but he doesn’t regret it and neither does Austin because it gave him the fire that he needed to become the star he became. It all worked out how it was supposed to. He continues by saying he didn’t handle it great, but he would probably react the same if it happened again, and I respect the honesty.

In Chapter Eight, he says the same thing when dealing with Ric Flair who went AWOL in April of 1998. Ric said he gave notice and was “entitled to take time off”, but Eric simply states he was in breach of contract. He couldn’t just pick and choose when he was to perform and there was a procedure in place to follow if anyone wanted time off. Ric didn’t follow it, and neither refused to budge, which is why things turned out the way they did. A lot of us are Ric Flair fans and want to take his side here, but again, this is different. We’re hearing this from an executive in charge, and it’s pretty simple with how Eric explains things, which is why he says again, “To this day, I would do the same thing”. If it’s in the contract, you have to eat shit and follow the rules. Otherwise, you have to deal with the consequences. His handing of Syxx made sense too, who later became X-Pac. Eric gives Sean Waltman credit as a performer but is sure to say “… when he was sober” before adding how these moments were few and far between. They had a verbal agreement on a new contract, they sent it to Waltman’s manager Barry Bloom and even started paying Waltman under these terms. A few months later, Eric is told from legal that Waltman didn’t sign it, so he called Barry to get him to do it. Barry wanted to talk about the terms despite them already paying Waltman with what they agreed on, so Eric got pissed off and fired him. Again, how can you not agree with Bischoff here? When you put yourself in Eric’s shoes throughout this book, you find yourself agreeing with him time and time again. This was a sleazy way to conduct business. Waltman agrees to the deal and then tries to renegotiate after he starts getting paid? Yeah, fuck that. I also loved the way Bischoff finishes this section with how it wouldn’t have mattered if Waltman had a “broken neck, cancer, AIDS,” or whatever else because he still would’ve fired him. Look, I like Waltman too, but Eric is right in that, “He wasn’t worth the pain in the ass he’d become”. Waltman used this to get himself over with the internet fans and dirtsheets by talking aloud about how Bischoff fired him. Considering these types of hardcore fans already didn’t like Eric, it just added to this growing idea of what people thought of Bischoff who didn’t actually know him or the context that surrounded each situation.

Perception can be reality to a lot of people. Austin trashed him to get over, Waltman did it, and so did Mick Foley. Even so, Bischoff tells his side of the story each time and I can’t help but see it from his perspective. Regarding Foley in Chapter Nine (“Unraveling; Shit Storms”), Bischoff just explains he didn’t want Foley to do all the dangerous stuff he did because it would be on his own conscience as a person. Naturally, Foley sees it as being held back, complains about it in ECW, they love it over there, and Bischoff is painted as the bad guy again. Again, tell me how this is Bischoff’s fault? If anything, this is an indictment on Vince McMahon because he let Foley completely destroy his body to the point where he had to retire as full-time wrestler in his mid 30s because he was so beaten up. Maybe Foley should have heard Bischoff out a little more, no?

Bischoff’s takedowns and analysis of Vince Russo (“He was a one trick pony and full of shit”) and Paul Heyman were on the money too. I don’t even hate Russo, but all his credibility as a writer is lost when he told Eric that he didn’t know what to do with Hulk fucking Hogan, and that he didn’t like the character or believe in him. He also lost a lot of respect for pestering Bischoff at his father’s funeral by calling him over creative decisions going into Bash at the Beach. What a jerkoff move, especially considering how he tried to do the production meeting by himself when Bischoff told him ahead of time to wait until he got there. I can’t defend Russo there. That’s some slimy shit just for not liking Hogan’s power plays. Look, we’re all ECW fans too, but Bischoff’s right to point out Heyman’s well documented integrity issues and how he’s so full of shit that he believes his own lies, especially after Heyman told everyone in WWE that Bischoff was on cocaine because Bischoff had to excuse himself a few times from their sit-down meeting to take some phone calls. Bischoff hilariously comments, “I guess he put one and zero together and came up with twenty-seven”. He straight-up says he didn’t give a flying fuck about Paul Heyman or ECW at the time, and he never stole talent from him. They’d call Eric because they weren’t being paid (accurate), he’d look at them and their situation and make the decision to hire them. It was business, but Heyman got over with everyone else by painting WCW and Bischoff as the devil. He’s not the first to do it, and he certainly wasn’t the last. I’ll say it again in that I respect Bischoff’s honesty, which is ever present throughout this book. Along with Randy Savage who was the most “paranoid” person he’s ever met, Eric’s thoughts on the “marginal talent at best” Lex Luger were warranted considering the many stories we’ve heard about him over the years (“…but between his lack of talent and piss poor attitude, I had no interest in him whatsoever, and I told Sting that”). His low-balling of Luger with the take-it-or-leave-it ultimatum because he had confidence in himself to think of another solution if he turned him down just shows you how good of a cutthroat executive Bischoff had the potential in being.

The section on Ole Anderson’s ideas being dated and unsophisticated (“He had zero understanding of the business side of wrestling”) was a great insight on what needed to change with early WCW too. In addition, Eric’s insight on every exec he encountered throughout his battles in WCW is everything we needed to know regarding his situation. No stone is left unturned.

Regardless, Eric did a great job all things considered. After reading the section on insecure egomaniac and bully Bill Watts and his archaic my-way-or-the-highway thinking that could be boiled down to being a flat-out refusal to evolve with the times, there shouldn’t be any question on who was the right man for the job. Tell Jim Ross he’s a suckass too, especially for claiming Bischoff got him fired when he wanted to leave after Watts’s exit anyway. Once the miserable JR got moved out of wrestling operations and into sales and syndication by Bill Shaw, his attitude worsened because he saw it as a demotion, despite him making the same money. When Bischoff suddenly got the new executive VP of programming job and jumped Ross on the ladder, he wanted out. Bill asked Bischoff what he should do, so Bischoff said he should let JR out of his contract if he was that miserable. Is that not doing the son of a bitch a favor? For Ross to claim he was fired unceremoniously is straight-up bullshit. He wanted to leave and asked to be let out of his contract! I’m not surprised that he used Bischoff’s name to get over just like the rest of them. Though Bischoff gives Jim Herd credit mostly because he hired Eric in the first place, he conveniently walks around Herd’s horrible creative decisions that led to Ric Flair leaving for a couple of years. Don’t get it twisted, Herd got rightfully fired too. This is just sliver of Eric’s subjective comments that I couldn’t take his side on. For example, Bischoff still refuses to admit he got worked by Brian Pillman in letting him out of his contract legitimately to build his character, only for Pillman to spurn him and go to the WWE after ECW. Let me be the first to say it Eric, you were one-upped here. On a few occasions, he continues to defend his work as the lead announcer of WCW out of necessity too, especially because of “radio face” Tony Schiavone, but I don’t buy it.

Considering how he was able to learn the ins and outs of TV production and was able to figure out the corporate structure of Turner at the time without any experience, I’m confident he could have taught someone to take his spot so he could focus on the behind-the-scenes stuff. I don’t think he had the goals of going to Hollywood, but he does admit he relished in the role of being the face of Nitro and that much is clear. He loved the attention, no matter what way he tries to explain himself. Fortunately for him, it worked out because he made seem good money as an onscreen character in WWE for years. He wouldn’t have been able to do that if he didn’t decide to stay on camera and be the lead authority figure of WCW. At the same time, he’s still wrong about the decision to take off Rey Mysterio’s mask, which he still argues is the way to go for some reason, and I wholeheartedly disagree with this assessment that Diamond Dallas Page could never be the guy to hold the world title and lead the company for long periods of time because he wasn’t on the level of a “Sting or Ric Flair in terms of status”. As head of creative, it was Eric’s job to get DDP there. Considering how well they built him up as a homegrown star and got him to main event level in such a short timeframe, there’s no reason to believe they couldn’t have put in the same amount of work to make him “The guy”. It’s Bischoff’s job to do it. He is the one who failed there.

Also, Hogan thinking that Sting looked like he was living in a cave going into Starrcade and that being part of the reason for him not wanting to put Sting over clean is ridiculous. If anything, the “cave-dweller” look fits the character. He didn’t need to be jacked. If there was ever a moment Eric needed to put his foot down, it was here.

Side note, I loved his doubling down of Madusa throwing the WWE Women’s Championship in the trash with, “If I’d have thought about it a little more, I probably would have put the title on a fat little midget and called it the “other” championship, but I didn’t think of it at the time. Damn it.” His take on Canada being “totally dependent on the United States. Their economy is completely dependent on ours. Their army and navy are nonexistent when it comes to being able to actually defend their country; they rely on the United States to do most of the job. If you look at the demographics of Canada, a large percentage of the population lives within a hundred miles or so of the border. Why do you think that’s the case? So, they can get the hell out of Canada as often as they can!” was uproariously funny. He’s such a heel! Him mentioning how Bret Hart couldn’t stop talking about the Montreal Screwjob and being unable to shake the baggage while in WCW was ironic as hell too, considering Bret is still talking about it in the present day.