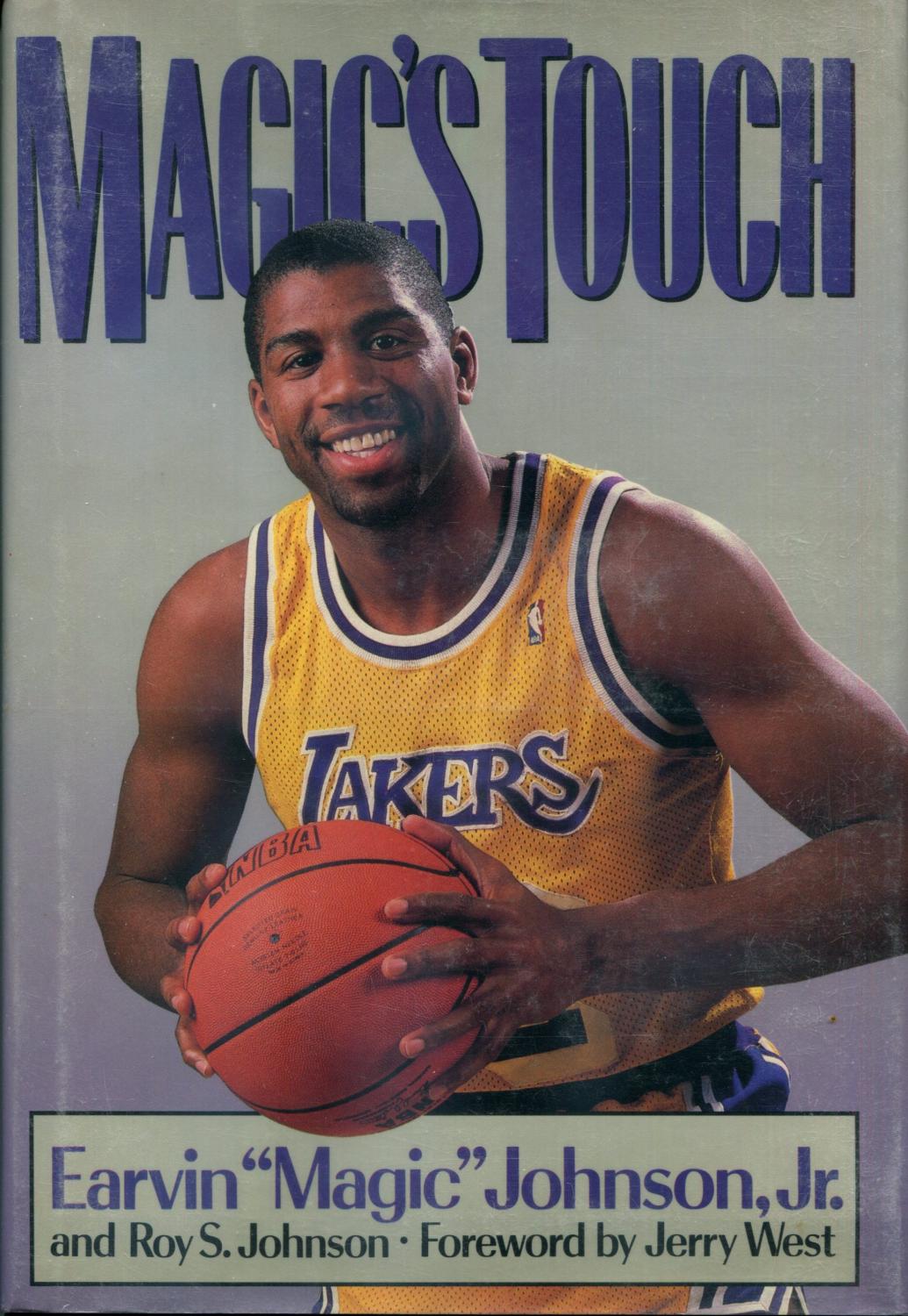

Written by Magic Johnson and Roy S. Johnson

Grade: C-

“We’ve all been blessed to be able to wake up every morning. And to me, that’s Magic”.

Summary

In the “Acknowledgements” section, Magic Johnson notes all of the coaches he’s ever had, his family, his editors, his agent, and others close to him. Following this is a foreword by another Los Angeles Lakers legend, Jerry West. Ever since the first time West saw Magic Johnson play at Michigan State, he was in awe, as Magic was a player he had never seen before. As we know was a rarity during that timeframe, Magic was the size of most centers but was playing point guard and was in complete command of the game. He was touching the ball on every possession and making all the right decisions. Even so, West admits he wasn’t convinced Magic could play the game his way in the NBA. Since West was in the front office at the time, the decision was up to him, and he was weary. At most, he could see Magic being a good power forward because of his size, though he wasn’t sure if sticking him in the low post so often would help or hurt him. At the same time, he wondered if Magic would get frustrated if he couldn’t make the adjustments. It’s been ten years now after these thoughts, and West states, “I’m almost embarrassed to admit I had my doubts”. Moving along, West talks about the word “greatness” and how it should only be attributed to a select group of players. Magic is one of these guys because of his ability to make others better. West goes on to talk about the Lakers’ success since drafting him and mentions how he told a friend that when Earvin Johnson Jr. was born, “he was sprinkled with Magic dust”.

He goes on to describe Magic as a “point guard who was as big as Bill Russell, as smart and creative as Tiny Archibald, and as exciting as Bob Cousy”. Above all else however was Magic’s smile. He had an enthusiasm for the game of basketball, and it’s looked at as a “direct impact on Magic’s ability to survive the various peaks and valleys of his career”. West goes on to mention Magic’s opening night, beating the Clippers on national television and jumping into the usually stoic Kareem Abdul Jabarr’s arms. Even when the Lakers lost to the Boston Celtics in the 1984 NBA Finals and Magic was blamed, he never lost the love and enthusiasm for the game, as they won the title the following year. Basketball just meant too much to Magic to be defeated. West talks about how great Magic’s work ethic is and how much he’s changed and improved his game since his days at Michigan State. He argues that other scouts doubted if Magic could retain his enthusiasm through the grind of an NBA season, but he proved everyone wrong. He even loves practicing. If anything, he hates being off the court and does everything possible to stay on it. In addition, West argues that Magic only attempts flashy play when it’s necessary or when they’re up a lot but ridicules the “flashy” label others have given him because it’s a bit overblown. Along with the fact that he has every basketball skill there is and how people can learn from him, West also states that Magic can teach others about winning.

“It’s the reason he plays the game, and the reason he’s, well, Magic.”

In the “Introduction” by Roy S. Johnson, we go back to the high school days of Magic, when he was still known as “Junior” to his family while still being “Magic” on the basketball court. Earvin Johnson Sr. wakes the teenage Magic up at 7AM on a Saturday, asks him how the game went (they won by 20), and tells him to now work on the truck. Earvin Sr. was the father of ten children in a working-class neighborhood in suburban Detroit. He had two full-time jobs, with a 5PM to 1AM shift assembling cars at the GM plant and a one-man (and son) hauling service that picked up garbage, branches, and everything in between. Along with this, he’d do a lot of side jobs and Magic would have to help from time to time, with Magic recalling a time when they had to go to an autoshop to soap down the floor from oil, let it dry, and then come back later and wash it down. Sometimes, Earvin Sr. would go in and scrub the concrete floors after his shift at 2AM, get a few hours of sleep at home, wake up to finish the hauling jobs, take a nap, then go back to the plant while the rest of the family would have dinner. He was all about hard work. Co-author Roy Johnson goes on about Magic’s high school basketball career. Though he was a phenomenon, he still joined Earvin Sr. on his hauling route, working before practice began at 10AM. It was mandatory for Magic, as was a job he had after practice where he stacked boxes at the corner dairy. There was yard work he had to do too. In the wintertime, Magic would have to shovel the driveway and the walkways, along with their neighbor’s. He couldn’t refuse either because Earvin Sr. was always working. If he wanted to do anything like go to the movies or something, Earvin Sr. would show him the ads in the newspaper to work and pay for it himself. He was always working.

We jump forward momentarily towards the end of the 1988-89 season. Magic got a hamstring injury in the NBA Finals, and the Detroit Pistons swept his Lakers to win the title. In his hotel room smiling to himself, Magic thought about those memories with his dad saying, “All those things paid off for me because I see it all so clearly now. I see everything he was trying to teach me. I look for nothing from nobody. Whatever I want, I work for”. Earvin Sr. always stressed the importance of school and working hard because he didn’t want to see Magic end up in a factory like him. Now, Magic is perhaps the greatest point guard of all time. When it’s time for him to enter the Hall of Fame, “It would be fitting that one other person also be inducted – Earvin Johnson Sr.”. Magic attributes all his success to his father because of him stressing hard work, leading by example with his two full-time jobs. Magic wasn’t going to go anywhere in basketball if he didn’t work for it, which is why he’s mad that he’s passed off as a “flamboyant player” because he’s seen as a guy who doesn’t work hard. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Co-author Roy Johnson talks about how there are “many professional athletes in a variety of sports whose skills aren’t defined by substance but camouflaged by flash”. However, flashy players only last a few seasons or so. Magic Johnson has endured because he’s much more than this label. Plus, he’s a winner. After this, Roy goes on about hypothetical dream matchups of Magic facing players of the past, and him stepping up in Kareem’s absence to play every position on the floor to beat the Philadelphia 76ers for the NBA Championship in 1980, his rookie season. It was just a year after winning the NCAA title with Michigan State, with the game between them and Larry Bird’s Indiana State being “widely recognized as the most significant in basketball history”. Two years before that game, Magic led Everett High School in Lansing, Michigan, to the state championship.

So, within four years, Magic guided his teams to championships on three different levels. That is a winner.

In the years since Magic’s first NBA Championship, he performed as if every season was ordained as the Lakers’ championship season. He talks about some of the teams’ failures like the 1984 NBA Finals, with Gerald Henderson picking off a pass to Magic from James Worthy, and Henderson subsequently scoring the game-tying basket that sent the contest into overtime where the Celtics won. The other being a lazy pass by from Magic to Worthy that Robert Parish stole as time expired. Suddenly, this specific series that may have been a “4-0 sweep was tied 2-2”. Following this, the Celtics won the rest of the games at home, taking the series and the title. Magic considers these moments the lowest of his career, though they won the championship the year after. Before that title, never in the history of the franchise had the Lakers beaten the Celtics in the championship. Kareem had the torch after getting traded from the Milwaukee Bucks and handed it over to Magic when it was time, with Magic taking over an extra responsibility on offense and winning his first MVP in the 1987 Season, with a second coming in 1989 when he beat Michael Jordan for it. At the same time, he helped the Lakers win two more championships, downing the Celtics and the Pistons in back-to-back years. However, last spring, the Pistons got their revenge. After being relatively healthy, Byron Scott suffered a torn hamstring during a practice drill that would take him out of the remainder of the playoffs. In Game 2, Magic tore his left hamstring, the same injury that sidelined him for three weeks earlier in the season. He tried to play in Game 3 with hopes that adrenaline would take over, but he could only get through four minutes of play before sitting out. He was done of the series, and so was the Lakers.

Even so, he never lost the perspective he had as a child when Earvin Sr. would still make Magic go through a list of chores. To finish things, he talks about the beauty and purity of Magic’s game and how it’s also simple and fundamental. He does all the right things and most of all, “it’s winning, winning, and winning again”. He gives Magic credit for making his basketball brilliance seem “so simple, so achievable”.

“That’s Magic’s Touch.”

In Chapter One (Your Game), Magic names Isiah Thomas and Mark Aguirre as his two best friends, and they both just beat him for the NBA Championship. He’s happy for his friends, but now, he’s hungry again to get back there. He truly believes if him and Byron Scott were healthy, they could have three-peated, something that hasn’t been done since the Celtics in 1966. Unfortunately, they both had hamstring injuries, so the Pistons swept them. Magic was bothered by the Pistons’ celebrating, and he thought about how Larry Bird sat out most of the season with foot injuries and the Celtics had their worst season since Bird got drafted. There are a lot of teams that will be gunning for the title next season, but Magic argues that nothing is better than the Lakers and Celtics battling it out in the finals one more time. It doesn’t matter who’s home court they’re on. When they face off, it still seems like they’re playing in the last game that’ll be played in basketball history. Everyone laughs and jokes before games, but when the Lakers are facing the Celtics, everyone on the team is quiet and ready to go to war. If they’re in Boston, Magic will stay in his hotel room most of the day and shut out any outside distractions. On some nights, people in Boston have snuck into the hotel and set off the fire alarm just so the Lakers players would lose sleep. In this 1989 Season, the Celtics were aging. With this and a combination of the Celtics not having many players to step in and take their place, and Bird’s ankle injury, their season was effectively stopped in its tracks. With Boston out, many more contenders emerged such as the Pistons and Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls. Magic goes back and reminisces beating Indiana State in the national title game, a season where Bird’s team was undefeated until their loss to Michigan State for the championship. Bird was unstoppable, with Coach Jud Heathcote said they defended Bird with “an adjustment and a prayer”.

They managed to hold him to 19 points and 2 assists though, and Magic saw Bird with his head in a towel, crying after the loss. Losing hurt Bird, a sign Magic attributed to a true competitor. In the NBA, Magic has faced Larry 34 times, with each one being treated like a national event. The Lakers lead 20-14 because of course he keeps count. Magic talks about their matchups in the Finals and once again takes the blame for 1984, admitting he “wasn’t mentally ready to handle the responsibility”. With this, he talks about how sweet it was to win the NBA Championship the next year on Boston’s floor, saying that it brought him closer to Bird than ever before. Before that, they just watched each other from afar, with Magic saying he would check the newspaper every morning to see how Boston did since they were gunning for the best record in the league. He’d even check Bird’s stats. During this injury-riddled season of Bird’s, he came into the Lakers locker room when they played Boston, and he talked to Magic after the game. Bird spoke about missing playing, how boring rehab was, and how he was hoping to play again in general. They always respected each other, but it wasn’t until the Lakers won in 1985 that they became closer as friends. Above all else, Magic wants that matchup one more time before he and Bird retire. Magic goes on to talk about Earvin Sr. being the best teacher in the world and talks about how he thought of his father when he won his MVPs. Earvin Sr. and Magic’s mom always taught Magic the value of maintaining a down-to-earth perspective on his life, and he calls them “Most Valuable Parents” for it.

Magic was in elementary school in Lansing, Michigan when Earvin Sr. taught him how to play basketball, showing him the fundamentals of the game. Earvin Sr. had very little free time Earvin Sr., but when he did, he would spend it talking basketball to Magic once he saw he took an interest to it. The most important thing he stressed was mastering the fundamentals. Now, back when Magic was a kid in Michigan, he was a die-hard Pistons fans. Because of this, his favorite player was Dave Bing. He was only 8 years old when Bing was the first pick in the draft coming out of Syracuse, but he was in awe of Bing who averaged 20 points a game as a rookie in 1966-67. The next year, Bing led the Pistons to the playoffs and the league in scoring. Pretty soon, all the kids at the park were trying to imitate Bing’s signature jumper. While watching Bing and the Pistons, Earvin Sr. would point out all the details to Magic like the footwork, head fakes, defensive stances, boxing out, and the things that separated the good from the great players. He talks about Bing’s jumper and how it was great because of his form and how he mastered how to do it the same way every time. These practice sessions with his father and learning all the fundamentals helped immensely. When Magic went to tryouts for the seventh-grade basketball team, the coach cut anyone who couldn’t make a lay-up with their opposite hand on the first day. It went from about 200 kids to 25 kids quickly. That day, Magic went home and thanked his dad. His father made him understand that it wasn’t just about watching NBA players and copying them without any thought. You have to think about all aspects of it and how they got there. How could he pass the ball to an open man without learning to see the whole floor and not just one area of it? How could he rebound without learning about boxing out? How could he score without using his left hand? With this, Magic focused and mastered the basics.

On top of this, Earvin Sr. noted he would have to learn how to do everything on the floor well. It didn’t have to be perfect, but just well enough to rely on whatever skill when he needed it. Learn to shoot so he has the confidence to shoot in the big games, learn to box out and rebound to help his teammates on the boards, learn how to play defense to stop his opponent, and learn to dribble with both hands and with your head up to get around pressured defenses. Magic had to make every pass imaginable to get the ball to an open teammate. Most importantly, he had to understand the concepts of the game so he could make the right decision. Some people make it to the league by just going one thing great, but he wanted to be known as an all-around player. To do this, he had to be fundamentally sound in each aspect of the game. Not perfect, just sound. His dad would remind him how his opponent will find a weakness and exploit it. He couldn’t hide, relating this to how his father wouldn’t let him hide from doing chores. Magic goes on to explain how all of his coaches treat him like everyone else, and he wouldn’t have it any other way. He didn’t get caught up in being a superstar. The game is about winning. It doesn’t matter who on the team wins the game. All that matters is that they won, and it’s very important to him. Every summer for the last few years, Magic has operated basketball camps in Detroit, Los Angeles, and San Diego. He gets kids from 9 years old to 17, and it’s been pretty successful. One of the campers he’s had was Kareem Jr., Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s son. At first, he wasn’t very good and was shy, with other kids at the camp giving him a lot of shit. By the second summer Kareem Jr. attended, he was better but still quiet. According to Magic, Kareem Jr. didn’t associate much with the other campers and never took it upon himself to be a leader. Then, everything changed for him in the third summer. All the kids were following him around and listening to what he had to say. Part of it was just growing up, but Magic thinks that the other part was the camp and the kinds of things he tries to teach the kids to bring that side out of him.

Magic gets reward out of these camps because not only does he get to teach basketball, but he sees how the kids change and grow. He’s learned a lot from it too like learning patience. Usually, Magic would get frustrated with his teammates or their complaints, but working with kids has helped him understand what makes people tick, and what makes them blend into a team instead of a group of individuals. Next, he talks about the shock of the young campers coming in since they think Magic’s camp is going to be all about fast breaks and the flashy play he’s known for, which couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s all about work. They’ll be in the gym early, and they’ll stay late. Some get scared, but nobody leaves. There’s only one way to play the game and that’s all out, pushing yourself as hard as you can for as long as you can. In addition to this, it’s all about the team. When the ball goes through the net, the team gets two points. A player hardly scores by himself, with Magic explaining the details of every possession in basketball thoroughly. He makes a good point saying, “To make any basket happen, somebody played good defense, somebody boxed out, somebody got the rebound, somebody hustled down the floor, somebody set the pick, somebody got open, somebody passed the ball, and somebody hit the shot. That’s a lot of somebodies, but a lot of somebodies equals a team”. This is the essence of Magic’s success. Basketball is a team game where “no one player is more important than the team”. He could score all the points he wants, but if his team loses by 1, he doesn’t have anything to be happy about. For an example, he mentions Bernard Kind dropping 60 on the New Jersey Nets on Christmas Day 1984 and being mad after the game because they lost. You have to win for the team and not yourself, something he tells his campers who are considered to be the “stars” on their teams back home.

Though I don’t really believe this, Magic says that the entire Lakers team from top to bottom considers themselves stars and how everyone plays a role in the team’s success. When they win a championship, everyone gets a ring, not just the MVP. Magic has also learned at his camp that he can’t be tough all the time. He believes in working hard because it worked for him, but he knows some of the younger kids are leaving home for the first time for his camp and he doesn’t want to scare them off. He relates this to a story when he heard the kids talking about how mean he was and how he doesn’t even smile, so he popped up out of nowhere, smiled, and yelled at them to get back in the gym. Even so, Magic argues that by the end of the camp, most of the kids want to stay longer and end up enjoying their time there. Once again, Magic stresses the hard work in practice. Since NBA players make the game look easy, most are surprised at how much work and dedication goes into being good. They don’t believe Larry Bird takes 1000 jump shots in the gym by himself before every game or that Mark Eaton studies films of opposing players for hours so he can understand their shooting habits to be a better shot-blocker. The game moves so fast that the casual viewer doesn’t notice or understand why a difficult move looked so easy. It’s all about the fundamentals and mastering them. He knows of the common criticism of him and Larry Bird not having great verticals, but they get by because of their fundamentals and hard work. This is why Magic makes his kids at his basketball camps run drills over and over again until it finally clicks. One thing he notes is that he has never tried to change a kid’s natural playing style. All he wants to do with his camps and this book is to “give young players a chance to see how good they can be, how far they can go in this game”.

There’s nothing wrong with taking something from someone’s game like how Magic did himself with Dave Bing. Even so, Magic never took away from what he himself did best and how he could help his team win. Some people have a natural way of dribbling and shooting, so trying to change their style rather than simply helping them with the fundamentals only makes players uncomfortable, which hurts their game. He points to Jamaal Wilkes’s and Michael Adams’s unconventional shooting strokes that still worked despite how they look. Magic keeps this in mind for his camps. He wants them to “be able to take what they do best on the basketball court and do it better“. No matter what way they may shoot or dribble, a small adjustment could make the world of a difference. Magic also adds how he sees kids make bad passes because they’re trying to be fancy before they’ve learned the proper way to make an easy pass, which is very common during the learning stages of basketball. Seeing kids shooting three pointers before they make a layup is another major issue, and a pet peeve of mine as well. It’s about understanding the technique and mastering it before you move up a level. This is also why Magic stresses conditioning because “a tired player will always look for the easy way out, make defensive mistakes, or probably lose concentration”. To Magic, there is no easy way to play basketball, which shows you the mindset of someone who is considered one of the greatest to ever play. Nevertheless, he didn’t always understand this. Back in high school, he tried to see what he could get away with from the coach. This time it was Coach Fox, and Magic admits this was an egocentric move on his part. Fox wasn’t about star treatment though. He treated everyone the same. One practice, Magic was playing around a bit and wasn’t going as hard as usual because he wasn’t in the mood. He ran everything at half-speed and tried to laugh things off.

Privately, Fox said that if he did this again the following day at practice, he won’t start the next game. This was Magic’s wake-up call. Never again did Magic cause such an issue at any level, according to him. Since then, he’s taken practice as seriously as the game and stresses the importance of practice to his campers. Being at practice an hour earlier than it starts only benefits him because he can work on his game without any interruptions. He says the more you love basketball, the earlier you should be at practice. The guys who do take it that seriously usually become the best players. When someone at his camp asks how long practice will be, he gets annoyed and says the game is “hourless” and “You go until the job’s done”. Discipline has been a big factor in his success. If kids can learn discipline, everything else will fall into place. Without hard work, Magic wouldn’t have become what he wanted to be. In Chapter Two (Seein’ is Believin’), we open with a game against the Pistons and how Magic processes the game in the halfcourt just by looking at player movement and matchups, ending with A.C. Green dunking on Bill Laimbeer and getting fouled on the play. Not only does he give Green credit, but he gives James Worthy and Byron Scott credit for reading the defense and executing the play just as they practiced it, allowing for Green to score. It was the team that made the play work. Magic reminds us that all of this action happened in about 15 seconds. Most novice people just see players crisscrossing along the court, someone taking a shot, and doing it all over again on the other end, but there’s so much more to it than that. Only basketball players and real fans can see how much goes into it. It goes by so fast sometimes because of great teamwork that you might miss part of a key sequence that opened the play for someone to finally score. Seeing the game from this perspective is something Magic attributes to Earvin Sr., who would point out the details when Magic was a kid.

Most importantly, he would show Magic how they looked in the early stages, so he would learn to recognize situations before the other players would. If he did this, he’d be able to take advantage of openings before the defense even sees them, and it allowed for Magic to start “seeing things before they happened”. To really get the true basketball experience when watching the game, Magic wants people to focus on the center. All the action revolves around this position. If they watch the man in the middle, they won’t miss anything. They’ll see the offensive movement, the screens, and picks teams use to get someone an open shot. They’ll also see defensive rotations and adjustments. If they only watch the basketball, they’ll miss a lot of the game on the other side of the floor, the weak side, things that ultimately “might be the reason the team with the ball either scores or doesn’t”. For the Lakers, everything revolved around Kareem from Magic’s first training camp in 1979 until the 1986-87 Season when Pat Riley restructured the offense around Magic. Even so, Kareem was the go-to guy in the clutch until he retired, arguing that they don’t win the title without Kareem hitting those free throws after Laimbeer fouled him. That foul was a weak ass call though, but I digress.

Regardless, Magic talks about how lucky he was to play with Kareem and how instrumental he was to the team’s success. To really watch a basketball game, Magic suggests the viewer pretend they’re the point guard to look for an opening in the defense, a weakness. They should see if they read the eyes of a teammate or notice a double team or whatever else. It can be fun, and the most successful basketball players at any level see the game in their minds. They size up situations, then see plays an instant before they happen. They’ve learned to look at the game differently from others. Some players that have gone into coaching get mad at others for not seeing the game the way they did, with Magic pointing to Lenny Wilkens, Willis Reed, and Doug Collins as examples. Their combination of talent on the court and how they saw the game differently from other players is what made them special. In his camp, Magic got frustrated because he had the same line of thinking too, and he came to the realization that he is one of these lucky ones who sees the game differently. He gives a great analogy here talking about how there is a book where everything is explained down to the smallest detail and illustrated with clear pictures. However, to a lot of people, the pictures in this hypothetical book are blurry. Even so, Magic says that if you’re able to visualize the game, then everything on the floor becomes crystal clear. Next, Magic talks about his love of the fastbreak and how real fans will ask questions as to why he passed it to a certain player in transition rather than another. If fans can anticipate what’s happening on the floor, this is having a “feel for the game”. Players have this, and they’ll use it when defending opponents. Also, Magic makes it known that most of the fanciest plays are done on instinct and are ingrained through concentration, practice, and dedication.

Fans also see when a team gets too comfortable with a lead and how noticeable it is. The Lakers did it in December 1988, blowing a 20-point lead to the Bullets. Then, he talks about all the other questions that players, coaches, and fans may ask during the game and why it makes basketball so exciting. Besides winning championships, Magic’s biggest reward is that he likes helping others enjoy it more, understand it more, or play it better in general. Every time a fan says to him that he helped bring them into basketball, he smiles because “that’s what this book is all about”. In Chapter Three (The World on a String), Magic talks about being ten years old and dribbling a basketball down the street. He’d do this every day, no matter where he went. He’d annoy the neighbors with his constant dribbling. The only place he wasn’t allowed to dribble was in the house, though he would break this rule from time to time. On rainy days, he’d play sock basketball and pretend to play while rolling up socks and shooting them. By the time he was in fourth grade, he was in four different leagues. Every day, he was somewhere playing. It would be the YMCA, the church, or the local rec center. He’d even play on Sundays after church. It allowed him to master his ball-handling skills. Magic then remembers when Earvin Sr. took him to see the Harlem Globetrotters and Harlem Magicians every year, and he was amazed at some of the tricks they’d do on the floor. It was a time when the NBA wouldn’t allow black players, and it was a shame because he thought Marques Haynes could’ve played against any of those players during this time. Magic defends himself from those who says he palms the ball and then gives credit to those who even amaze him at what they can do with the basketball like Isiah Thomas, Kevin Johnson, and Mark Jackson. Since they’re smaller, they can get low and dribble through the gaps but since he’s bigger, he has to just push through them instead.

Moving along, Magic says a player can always learn a new skill. When they stop wanting to learn, they’re usually out of the league. During every offseason, Pat Riley sends each Laker a letter telling him the areas of his game he should work on over the summer. He doesn’t demand it, but it’s a strong suggestion and he’s rarely wrong. Magic attributes Riley’s letters as to why they’ve won championships, as every player followed it and improved their game. He gives examples like A.C. Green’s initial inability to dribble around his man. Now, he can start the fast break by himself. All Byron Scott could do was shoot, but he couldn’t put the ball on the floor and drive. When the defense played him tight because they knew this, he’d shut off. Now, he can pump fake and go to the hole. In doing so, it gives the Lakers more options on offense. Speaking of dribbling, he stresses keeping your head up, and he chalks up his 2700 turnovers as to times he wasn’t looking, or his eyes weren’t open to what he was doing. Though mathematically, he only commits a turnover every 10 minutes of play, Magic reminds us that one turnover at the wrong time can lose the game. Another important aspect of dribbling is positioning. He tries to get as low as he possible can to protect the ball. Then, he can use his other hand as a shield. This way, the defender has to go through him to get the ball and it will be called for a foul. Then, there’s also footwork and how he positions his body, with Magic noting that he likes to keep his feet a shoulders’ width apart. Guys like John Stockton, Maurice Cheeks, and Mark Price have their legs spread wide and knees in perfect position, which is why they don’t commit a lot of turnovers. After going on about Isiah Thomas’s penchant for going between the legs a series of times to freeze a defender and going right past them, Magic talks about the third element of dribbling. This is keeping the basketball on your fingertips because it’s the most sensitive area, forcing you to use a delicate touch with it.

He brings up two drills you can use to develop your dribbling skills such as the six-inch drill and the figure-eight drill, two routines that basketball players should be well aware of. To strengthen your fingers and to maintain control when someone tries to steal it, Magic also suggests the wall drill. Magic’s Touch continues in this format, with Magic detailing his approach to the game while showing how others can learn through his perspective by bringing up specific instances from his life and career.

My Thoughts:

Magic’s Touch isn’t the book you think it is. It was never going to be a tell-all exposé like Dennis Rodman’s Bad As I Wanna Be because that was a rarity during this time period of the NBA, but something a little more in-depth doesn’t feel like asking for too much. From the perspective of Magic Johnson, Magic’s Touch is part autobiography, part instructional guide on the game of basketball, and part insincerity masked as inspiration. Though it’s possible that the latter is just my ingrained pessimism regarding superstar celebrities and their need to write a book simply to have another source of revenue while they’re at their most popular, the content of Magic’s Touch cannot be ignored. As opposed to Rodman who didn’t care at all what people thought about his opinions on the game and others, Magic takes the exact opposite approach in an almost groan-inducing way. He writes this book like Commissioner David Stern was standing over him and watching him type every word, with Magic looking back at Stern for an eventual nod of approval. Context is important though. This book did come out in 1989. This was before Magic announced he had AIDS, before he retired, before he came back, and before he retired again. Magic’s Touch came out right after the Lakers lost to the Pistons in the NBA Finals in 1989, so all Magic is thinking about is how he’s going to get back to the dance. Blowing a hole through the league and trashing teammates, players, or league officials was never going to be what this book was nor was this ever Magic’s style, or at least what we know about his public persona. At this time, he still had a squeaky-clean image and a smile to match one of the NBA’s most popular franchises. With this being said, at times, Magic’s book comes off much like Hollywood itself, phony.

For all intents and purposes, this is a nice book when you keep in mind Magic’s apparent goal, as he makes it clear early on that he’s trying to teach fans about basketball, instill a passion for the game, and winning the right way. In doing so, he brings up examples from his career and life to match his advice and approach. If this was always the purpose of the book, I suppose he did this job well. On the other hand, as much credit as we can give him for being earnest and thoughtful in his goal, we also have to acknowledge that the book starts to tread water around the halfway point and never dives any deeper than what he alludes to in the first half. Basically, Magic’s Touch is way too safe for its own good. Anytime you want him to go deeper with his opinions and talk about certain moments in his career or personal life, he touches on it but barely scratches the surface, rarely going further than what basketball fans already know or can learn with minimal research. For example, the most important part of his career up until this point was his fallout with Coach Paul Westhead in 1981. Besides this, Magic doesn’t have a lot of controversy attached to his name, so hearing his side of the story for what was almost a career-altering decision could be huge for a book like this. Going along with the theme, it could also double as a valuable lesson for young basketball players who also have disputes with their coaches or how things are done on their respective teams. Giving us a measly paragraph or two is really underselling it to the point where you’re frustrated. You’re telling me Magic couldn’t give us a little more detail about his situation that led to him requesting a trade and Westhead being fired? This is a pretty big deal! He barely touches on it, says he has no problem with him and regrets it, passes it off as a difference in opinion, and then he says he’s happy seeing Westhead do well coaching college basketball knowing he played a part in ruining his NBA career.

In Magic’s defense, Westhead was a fucking moron with the way he approached the Lakers, and they got as far as they did in spite of him, along with the fact that Jerry Buss planned on firing him regardless of Magic’s decision. Even so, there had to have been more to this story other than Magic vehemently disagreeing with Westhead’s system that he was so insistent on implementing no matter if it fit the playing style of his roster or not. You don’t demand a trade two seasons into your career if this is the only disagreement they had. Why is Magic playing this nice about it? What else did Westhead do? What did management think of him? What did his successor Pat Riley think about him? How did the other players react to him, especially since no one else requested a trade but Magic? It’s stuff like this that ruins the potential of Magic’s Touch. Is it an autobiography? At times, it felt like one, which is why the first half of the book was somewhat compelling, mostly because it felt like it was leading to something while motivating the reader to work hard. This is the stuff Magic does right. As athletically gifted as he is, Magic details enough about his life to show us how hard he’s worked to get where he was at and how much he took from his hard-working father. His obsession with playing the game every chance he got, along with his obsession in winning and playing the game correctly, led him to greatness. Only the greatest of the great see their potential and do everything they possibly can to maximize their potential, and this couldn’t be more true when describing the career of Magic Johnson. In his own words, it’s clear he didn’t just luck into a career like this or that he’s playing the role of a coach talking to youngsters looking to follow in his footsteps, though that is technically what he’s doing. He just knows what worked for him and is relaying this to anyone who will listen.

Unfortunately, you just want more. Maybe it’s an age thing. If you’re younger and still a novice to the game that has become enthralled with the stars of the NBA, a phase every basketball fan goes through, you may appreciate a narrative like this, as it will temporarily satisfy your hunger to learn more about the game and to dedicate yourself to it. If someone like Magic Johnson works this hard to win at every level, there is no excuse for you. He had the same attitude watching his father work two full-time jobs, and he carries this humbling reality with him while at the top of the league. It’s what makes a good player great. He could take a bit of a backseat or not take things so serious because of what he’s accomplished thus far, but his desire to play winning basketball at all costs will not let him. This alone can inspire a kid reading Magic’s Touch. Some of his words of wisdom could also be useful for those wanting to be coaches, especially at the smaller levels. There is a lot of content that can be taken out of it and used to motivate the next generation of hoopers in need of it. It’s just the in-between demographics that may not maintain interest. At first, the audience seems to be for all ages, with enough to satisfy younger readers and adults alike, especially in the first half. However, the content gets progressively more childish and less about Magic himself. This is where certain age groups reading this will start to tail off. At one point, he starts explaining the basics on an elementary school level like “Another shot people take for granted is the lay-up” while overanalyzing one of the most basic shots in basketball. This is why it’s so hard to decide who this book is for. If you don’t know the importance of a layup by the time you’re 12, I don’t know what to tell you. For adults reading, you just ask yourself, “Really? Yeah, no shit”. Actually, there are a lot of lines and sections in this book that will have you reacting like this. In fact, he wastes six fucking pages on basic stretches accompanied by drawn pictures of himself doing them.

Again, what is the target audience? How would anyone not know this? They aren’t even complicated stretches. They are all one’s that you are guaranteed to have learned in gym class. He does this again with his overly complicated explanations on certain passes, how to do them, and what situation calls for it. Then, he’ll say something you’ve heard the first time you may have attended your first practice like “You don’t want to foul someone shooting from long range” or “Play good defense without committing a foul”. Again, no fucking shit Magic!

Speaking of a waste, did Magic really need to put his stats at the end of the book when all he talked about was how this didn’t matter and how it’s all about winning?

Though Magic does get some points for certain lessons like talking about the importance of mastering close-the-basket and midrange shots before you shoot from long range (because it’s a problem many players still have today), he’ll ruin things by cookie-cutter “NBA role model” comments like during his chapter on referees. In a comment that is written like there is an American flag behind him, Magic literally says, “I believe it’s important to respect the officials, as much as that might be difficult at times. Players always believe they’re getting a raw deal from the refs. In most cases, we’re wrong”. It reeked of a star sucking up to the league, knowing they are aware of his book being published. Even when he talks about a time when he was ejected by the refs during a game against the Phoenix Suns, he just talks about letting his teammates down like some sort of boy scout. Magic’s “running for public office” comments don’t stop there either. When talking about offseason workouts to stay in shape, he talks about swimming and cycling. In regard to cycling, he makes sure to tell the reader “It’s safe as long as the rider wears a helmet and follows the traffic laws”. Did his fucking lawyer write this? Don’t you think something like this is already implied? Even in his closing remarks where he practically makes up a basketball-related version of the Pledge of Allegiance (“It means…”), he randomly throws in towards the end to not use drugs, saying “I’ll get high on basketball”. I got to tell you, if this was in the opening paragraph of this book instead of one of the final couple of sentences, I would’ve closed it. Coming up with your own personal doctrine to inspire dedicated winning basketball for young learners isn’t a bad thing, but at some point, you can’t help but say, “Dude, shut the fuck up”.

The insight Magic does give about himself, or others are enough to whet the appetite, but it just leaves us wanting more because you know he’s holding back. Okay, learning about how Kareem never taped his ankles because he was that confident in his yoga routine was interesting, as was Magic’s offseason workout being running in the sand (not necessarily surprising but you wouldn’t know this otherwise), Magic stopping eating red meat on a regular basis 5 years after he joined the league, Magic being scared to take the last shot when he was younger, Pat Riley’s grading system for his players, or Riley’s end-of-the-season letters to note what each guy needs to improve on, but what about all the other stuff? Magic says specifically that egos kept the Lakers from winning in 1981 and 1986, but who’s egos is he talking about? He generalizes it, doesn’t name anyone specifically, and then calls out their issues with complacency. There had to have been more to it than that! He doesn’t need to snitch per say, but there’s a way of explaining things in detail without sounding unprofessional. Magic played a lot of games in high school and college, but he only mentions the national title game over and over again. Wasn’t there anything else he took away from all of those other games he was involved in? Kareem just accepted with no resistance that he wasn’t the first option anymore? That’s what Magic makes it sound like but for someone as good as Kareem was for that long, there had to have been more to this story! There’s very little on the seasons where they didn’t win the championship too. Isn’t there anything to touch on there? There had to be some frustrations with players or schemes or opponents or whatever else, but Magic never goes any deeper with it. He just moves along and brings up how they figured whatever minor thing out and won the next year. Wouldn’t learning more about the down years at the same time help readers just as well as the winning seasons?

What about all the opponents and rivalries he may have? All he does is give credit to other players and calls them talented and how they’re solid competitors, but he never goes into detail. In the “Inner Game” chapter that focuses on the game-within-a-game between every matchup, full-on details of his one-on-one with opposing point guards around the league would’ve made a great deal of sense to give us insight into who they are from his perspective, but he just gives a runaround “They’re very good” type of comment that has a lot less substance that any reader would be satisfied with, though I do appreciate the credit he gives Mark Eaton because he was underrated as a rim protector and should be talked about more. At most, Magic talks about how “There are some guys in the league who are better actors than players” and relates this to Bill Laimbeer and his flopping, but that’s it. No one is asking Magic to start hating on everyone because again, this was never his style. Even so, he has to have more of an opinion on this stuff than he leads on! The only time he seems bothered is the Lakers being referred to as “Showtime” because it never talks about how good their team defense was and how it gives them the unofficial moniker of being “soft”, but he never gets angry about it. He just explains in great detail how good their defense was, which I suppose is a fair and dignified way of responding, but it’s just not that entertaining from the reader’s perspective. The other time he gets a bit agitated is when he talks about people saying Larry Bird is a better shooter than him because he never got the chance to prove himself as a shooter in the flow of the offense. Well, even when Pat Riley restructured the team’s offense to make Magic the first option (where he did have his best season as a scorer), the people are still right.

Bird was always a better shooter. It’s an unequivocal fact.

Magic tries to argue that up until the 1986-87 Season, the other guys on the team were the stars and his job was to just set them up, but that’s absolute bullshit and he knows it. Magic was a star from the outset. That’s common knowledge. There’s being modest and just plain lying, and this was the latter. Even when Magic “proved” himself as a shooter in his MVP season, he’s still wrong. His form on his jumpshot was always laughable, so his instructions on how to shoot are a moot point. His offensive game relied completely on the fast break, posting up, and floaters near the rim. He was never considered a good shooter because he wasn’t. He just did what he could do very well. Most defenses led him shoot. Sure, he proved Caldwell Jones wrong in the 1980 NBA Finals, but any basketball player knows you can get hot from time to time. Magic could never shoot like that on a consistent basis, especially not on Bird’s level. It just wasn’t his game, even when he was the first option. Also, Magic states, “I think players, in general, used to be more well-rounded”, which is something Dennis Rodman expressed as well years later in Bad as I Wanna Be. He could have gotten half a chapter with this statement alone by explaining his reasoning, but he just says it and moves on to talk about why it’s not a big deal because it works for others and how he is still well-rounded. If it works for others, why should we follow him? Considering how Magic stresses the entire book about how you have to master everything in the game, why would he contradict himself by agreeing that mastering one skill can still get you there? It just undermines one of the biggest themes of the narrative!

Despite the irritation that can come with his teachings on the game, Magic does make a lot of good points that are worth talking about too, which is why there’s still some value in this book. When talking about Game 6 of the 1980 NBA Finals, he talks about how they were the underdog in that game because Kareem was injured and “In sports, the underdog always has the advantage because the favorite must cope with the pressure of having to win when they’re supposed to win”. He’s right on the money with that one, so you do get nuggets of wisdom from time to time that are worth mentioning on his end. For instance, as a point guard, getting to know your teammates and their games are very important like how they like to catch the ball and how good they are at catching certain passes. With this, Magic details how Kareem will work hard to establish position in the low post but if he had to go get the ball, he wouldn’t. James Worthy had great hands and would throw signals as to where he wanted it, and A.C. Green doesn’t catch it well in traffic, so there’s no point in giving it to him during this situation. Then, there’s the importance of passing in general because “everyone was happier when they got a piece of the action”, a very accurate statement that explains why one player can’t do everything and still win. A big shout out to James Harden, as he exemplifies Magic’s “I-Got-Mine-Theory”.

Little details like this from Magic are pretty cool, and his section on rebounding is something that the younger generation should read. He’s right. It is the ugliest part of the game, and you have to have the heart and desire to be a rebounder. It’s just like how Dennis Rodman talks about it in Bad as I Wanna Be, it has to be in you. It’s not about being tall. It’s about heart and desire. Magic admits he was never interested in it when he was younger because it was easy due to his height, but it gets harder when everyone else’s size catches up in the big leagues. Above all else, he stresses how important the correlation is between rebounding and winning, bringing up how Pat Riley is adamant on this fact and gets more mad about the players’ efforts for a rebound rather than actually getting it. It’s “a matter of wanting to be a good rebounder”. That’s the real battle. This is a very good point because you’re not going to get every rebound. Nevertheless, not trying to get it is a much worse offense. If winners like Pat Riley and Magic Johnson are stressing it, you know how important of a takeaway this is. Then, there’s defense, as Magic brings up a very valid point with how there’s no excuse for inconsistency on defense. Sometimes on offense, you just can’t hit. It happens, but defense is entirely effort and conditioning based. There really is no excuse. When you combine this with the fact that every coach Magic has had stressed defense over offense and he’s won at every level, it only strengthens Magic’s point.

Hey, Mike D’Antoni! Are you listening?

His discussion with a camper on how to approach a fast break and how you truly have to have “100 eyes in your head” was a great way to detail how advanced of a basketball mind Magic has, as he spouts comments on positioning and matchups and analyzes them in seconds while on the break. The same can be said for his section on how to communicate on the court and read signals as a player, while going through hypothetical and real plays to present how to go about this. His thoughts on conditioning can change your mindsight too because you should only want to think about the game when you’re playing it, not how you need to catch your breath. Losing a game because you’re tired does seem silly when he puts it like that. It makes you look in the mirror and ask yourself if you really want to win or if you want to take shortcuts like a lot of nonwinners do. For not being a great individual defender, his advice is sound, such as being balanced and not out of control because it will be easier to be faked out of your shoes, as it’s something not a lot of young players realize. Sometimes, they are too intense and stop thinking, and it can cost them against a good player. Additionally, blocking someone’s shot should be a player’s last resort because it’s so difficult to do (this should be basketball 101 but people do forget this), and there is a decent discussion on handchecking. Though it’s illegal, he does admit that you can get away with a nudge here and there. In doing so, it can make a world of a difference in a shooter’s timing, with the amusing example of Norm Nixon fouling Maurice Cheeks on every possession in their Finals matchup but never being caught highlighting this. Of all the coaches and their styles, Magic’s description of Jack McKinney sounded the most glowing, despite their lone season together. His description of McKinney watching every player and creating a well-balanced system that fit everyone’s needs seems like what every coach should do, but real basketball players with years of experience are very aware how this is not always the case.

Without naming Westhead, he compliments McKinney because he didn’t ask the players to do anything they couldn’t for the sake of some “theory”. You have to love that. System coaches can be infuriating to watch. It can be downright ignorant at times. Coaches need to be flexible and adjust to their rosters. Otherwise, teams can gameplan for them too easily.

Again, shout out to Mike D’Antoni.

What I also found rather interesting was that even in 1989, Magic Johnson admits the charging/blocking call is the hardest to make in basketball. The fact that it’s still a contentious argument for fans and analysts alike shows you there is no defined way of calling it even with the rules in place. Honestly, argue it every single time you’re playing organized basketball. Nobody fucking knows what the real answer is. It’s too fluid.

When I say that I see insincerity, or things not being entirely truthful within this book, it’s showcased with how Magic makes EVERY aspect of basketball sound like the absolute most important thing in the world and makes himself sound like the perfect player who understands and agrees with every decision and agrees without question EVERYTHING the coach does, and that’s just not true! No matter how good you are and no matter how much you may win at that level, there’s no way you’re still completely fine with everything that has ever happened in your career! That is the most infuriating thing with Magic’s Touch. I get that he’s a positive person, but he’s holding back way too much, and it becomes too noticeable with how much he sucks everyone’s ass. For example, he knows damn well that the role of the bench-warming reserves isn’t as big as the stars’. He’s just saying that to make kids feel better and more cooperative in general. Sure, bench players need to be ready for their opportunity, but the reserve that claps for the others and barely plays? He’s objectively less important than the others, and it’s okay to admit that. If anything, Magic should just inspire them to work harder to find a way into the rotation. Kids may not be able to see through Magic’s false hope, but anyone over the age of 15 can. At what point are you insulting the reader’s intelligence?

For younger fans of the NBA and 1989 in general, Magic’s Touch is good. For today’s standards however, it’s a substandard book that is so encouraging and enthusiastic, it becomes unbelievable. Some of Magic’s takes on the game and the details of his career can be compelling and authentic, but a lot of the time, it has such a lack of substance and is so straightforward and obvious, you’ll roll your eyes to exhaustion. I’d even argue that the older you are, the less you’ll like the book. Of course, unless you’re an aspiring coach.

+ There are no comments

Add yours